The Sinking and Wreck of the

Wilhelm Gustloff

January 30th, 1945

Wilhelm Gustloff

January 30th, 1945

Kriegsmarine blanket saved from the sinking Wilhelm Gustloff - January 30th, 1945 - 9:00pm

When the torpedoes from the S-13 exploded against the Gustloff, passengers began the stampede to escape the sinking liner. One of the male passengers was sitting in the cabin he shared when the liner was hit. Knowing the temperature outside, he bundled up and grabbed a Kriegsmarine blanket which was nearby. As the ship listed, he managed to climb into a lifeboat with the blanket wrapped around him and was lowered into the freezing sea. A few minutes later, the Wilhelm Gustloff disappeared forever beneath the Baltic waves. He was rescued from the water by the T-36 commanded by Capt. Robert Hering and taken back to land with the blanket still wrapped around himself. During the years, he kept it stowed away and when he died of cancer, it was inherited by his son. Eventually, he anonymously turned it over to a German auction house in 2008 to be sold along with other items from the personal collection.

At right is said blanket which we acquired for our Wilhelm Gustloff collection. This piece was purchased on November 22, 2008 at a military auction from Dresden, Germany from the Alschner Antique House. The letter which accompanies it is as follows:

"This article concerns a bog standard Kriegsmarine blanket from WWII, which belonged to a survivor of the ship Wilhelm Gustloff. Who struggled onto a lifeboat with this blanket during that fateful night, whose occupants were subsequently taken on board and rescued by a German torpedo boat, which I have been made aware of by his son. Sadly, his father - the owner of the blanket - died some years ago due to cancer. According to the son, the commander of the torpedo boat, Hering, rescued some hundred survivors..."

The blanket is a grey wool/rayon blend which measures 6' 4" long and 4' 4" wide. It has a 4" wide interwoven red stripe positioned near each end. Both the side edges of the blanket have the typical, tightly woven, interlocking, reinforcement threads to prevent fraying. One side of the blanket has the hand, chain stitched, script, "Kriegsmarine", in red cotton threads. The script is also visible on the other side as a mirror image. There is one large hole and several small ones (whether caused by moths, age, or from the sinking is unknown.)

All records from the auction, including the note stating the blanket's history, remains in our archive. The above description is a general translation from the German letter. An emotional piece which was on board that night and survived the worst sinking in history.

When the torpedoes from the S-13 exploded against the Gustloff, passengers began the stampede to escape the sinking liner. One of the male passengers was sitting in the cabin he shared when the liner was hit. Knowing the temperature outside, he bundled up and grabbed a Kriegsmarine blanket which was nearby. As the ship listed, he managed to climb into a lifeboat with the blanket wrapped around him and was lowered into the freezing sea. A few minutes later, the Wilhelm Gustloff disappeared forever beneath the Baltic waves. He was rescued from the water by the T-36 commanded by Capt. Robert Hering and taken back to land with the blanket still wrapped around himself. During the years, he kept it stowed away and when he died of cancer, it was inherited by his son. Eventually, he anonymously turned it over to a German auction house in 2008 to be sold along with other items from the personal collection.

At right is said blanket which we acquired for our Wilhelm Gustloff collection. This piece was purchased on November 22, 2008 at a military auction from Dresden, Germany from the Alschner Antique House. The letter which accompanies it is as follows:

"This article concerns a bog standard Kriegsmarine blanket from WWII, which belonged to a survivor of the ship Wilhelm Gustloff. Who struggled onto a lifeboat with this blanket during that fateful night, whose occupants were subsequently taken on board and rescued by a German torpedo boat, which I have been made aware of by his son. Sadly, his father - the owner of the blanket - died some years ago due to cancer. According to the son, the commander of the torpedo boat, Hering, rescued some hundred survivors..."

The blanket is a grey wool/rayon blend which measures 6' 4" long and 4' 4" wide. It has a 4" wide interwoven red stripe positioned near each end. Both the side edges of the blanket have the typical, tightly woven, interlocking, reinforcement threads to prevent fraying. One side of the blanket has the hand, chain stitched, script, "Kriegsmarine", in red cotton threads. The script is also visible on the other side as a mirror image. There is one large hole and several small ones (whether caused by moths, age, or from the sinking is unknown.)

All records from the auction, including the note stating the blanket's history, remains in our archive. The above description is a general translation from the German letter. An emotional piece which was on board that night and survived the worst sinking in history.

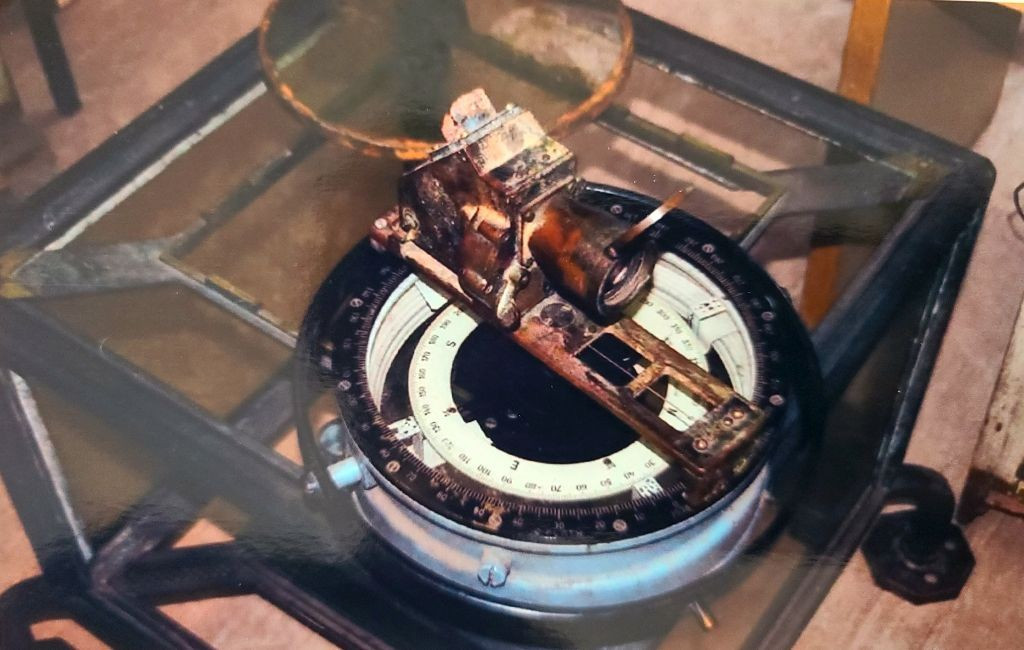

Artifacts recovered from the wreck of the Wilhelm Gustloff - 1980s

Photographed at right are four artifacts which were recovered from the wreck of the Wilhelm Gustloff in the 1980s by Polish sport divers. During this time, several divers went to the wreck gathering everything from hand rails and decking to portholes and interior effects. Recovered before diving limits were imposed upon the wreck, these, along with several other artifacts were divided up by said divers. One of our contacts in Germany, who is also a Gustloff collector, purchased several pieces for his personal collection. In 2009, we acquired and transferred these artifacts over to our Wilhelm Gustloff exhibit. They are as follows:

1. Medium Glass Bottle

- Used for medicine out of the ship's pharmacy, measures 15cm high with the marking "200" on the bottom. Left 'as is' from the wreck, still contains sediment inside and out. Very good condition.

2. Porcelain China Pot

- Probably a family piece from one of the fleeing refugees onboard, measures 8.5cm high, 9.5cm on the top from spout to handle edge. Originally had four painted scenes, one on each side. Two have been completely erased by the seawater, one is badly faded, and the final scene of a windmill is still intact, but damaged. Gold trim around the top and scenes is faded or missing, 1.5cm chip and hairline crack to the base present on the side with the intact painting. Left 'as is' from the wreck, contains sediment and rust throughout.

3. Small Glass Bottle

- Used for medicine out of the ship's pharmacy as well, measures 11cm high with the marking "R" on the front. Left 'as is' from the wreck, still contains sediment inside and out. Very good condition. (Images of the Wilhelm Gustloff's on board pharmacy can be seen to the right.)

4. Silver Fork

- Smaller 15cm cake or dessert fork in remarkable condition. Plain design aside from a small decoration in the middle of the piece. Because there was no damage to the piece aside from tarnishing, it has since been cleaned to its original condition. It is amazing how well silverware can cope underwater. The silverware in the RMS Republic museum photo fared even better than this for having been submerged for twice as long.

Photographed at right are four artifacts which were recovered from the wreck of the Wilhelm Gustloff in the 1980s by Polish sport divers. During this time, several divers went to the wreck gathering everything from hand rails and decking to portholes and interior effects. Recovered before diving limits were imposed upon the wreck, these, along with several other artifacts were divided up by said divers. One of our contacts in Germany, who is also a Gustloff collector, purchased several pieces for his personal collection. In 2009, we acquired and transferred these artifacts over to our Wilhelm Gustloff exhibit. They are as follows:

1. Medium Glass Bottle

- Used for medicine out of the ship's pharmacy, measures 15cm high with the marking "200" on the bottom. Left 'as is' from the wreck, still contains sediment inside and out. Very good condition.

2. Porcelain China Pot

- Probably a family piece from one of the fleeing refugees onboard, measures 8.5cm high, 9.5cm on the top from spout to handle edge. Originally had four painted scenes, one on each side. Two have been completely erased by the seawater, one is badly faded, and the final scene of a windmill is still intact, but damaged. Gold trim around the top and scenes is faded or missing, 1.5cm chip and hairline crack to the base present on the side with the intact painting. Left 'as is' from the wreck, contains sediment and rust throughout.

3. Small Glass Bottle

- Used for medicine out of the ship's pharmacy as well, measures 11cm high with the marking "R" on the front. Left 'as is' from the wreck, still contains sediment inside and out. Very good condition. (Images of the Wilhelm Gustloff's on board pharmacy can be seen to the right.)

4. Silver Fork

- Smaller 15cm cake or dessert fork in remarkable condition. Plain design aside from a small decoration in the middle of the piece. Because there was no damage to the piece aside from tarnishing, it has since been cleaned to its original condition. It is amazing how well silverware can cope underwater. The silverware in the RMS Republic museum photo fared even better than this for having been submerged for twice as long.

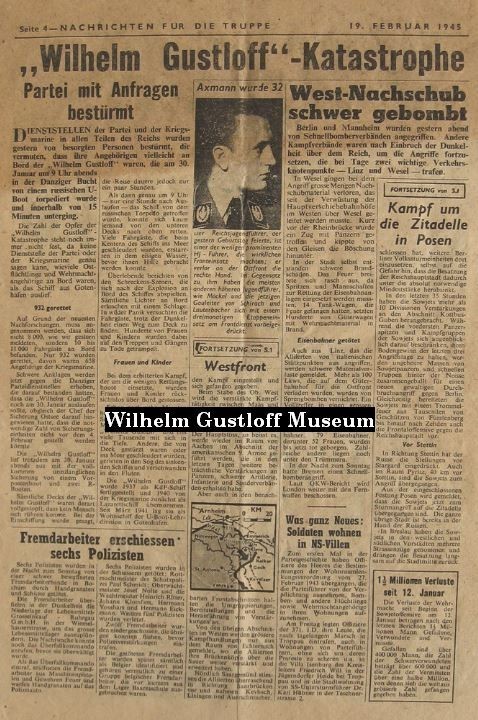

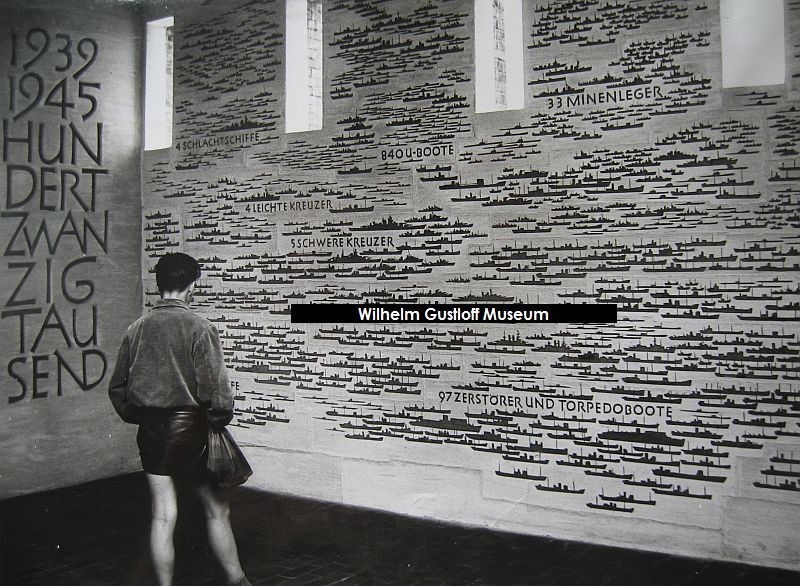

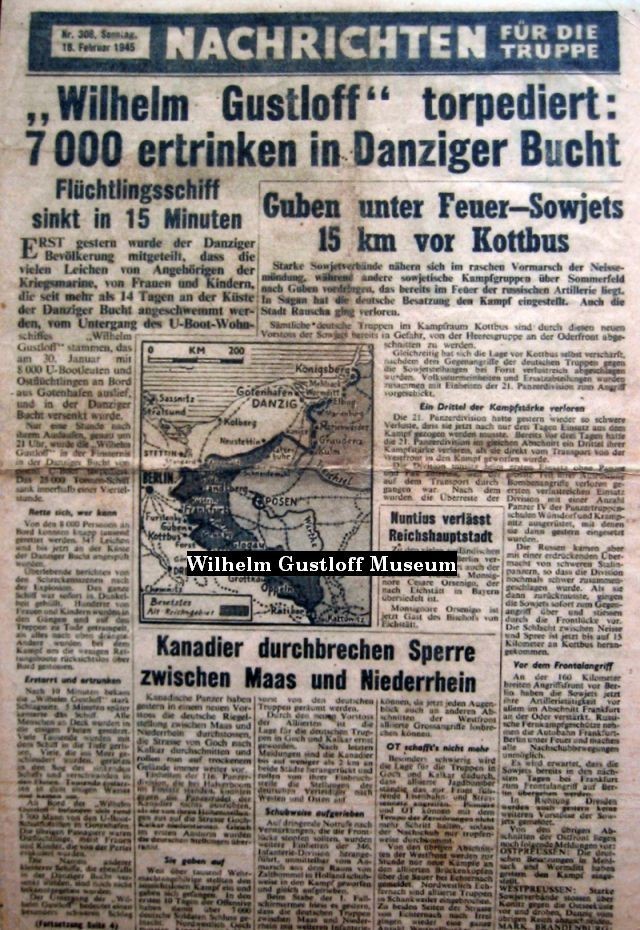

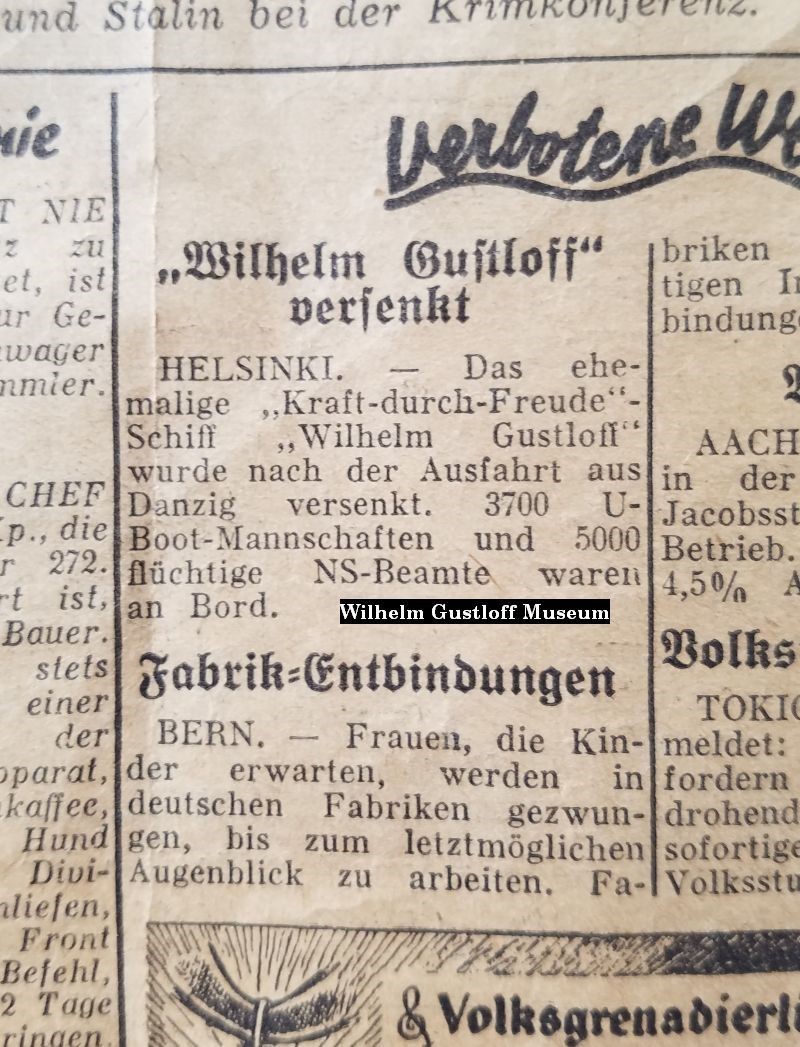

"Wilhelm Gustloff" - Disaster

Party stormed with inquiries

The offices of the Party and the Navy in all parts of the Reich were yesterday stormed by anxious persons, who suspect that their relatives were perhaps onboard the "Wilhelm Gustloff", which was torpedoed by a Russian submarine on January 30th at 9:00 pm in the Danzig Bay and sunk within 15 minutes. The number of victims of the "Wilhelm Gustloff" disaster is still not certain, since no office of the Party or of the Kriegsmarine can accurately say, how many Eastern refugees and members of the Wehrmacht were on board, when the ship left Gotenhafen.

932 saved

On the basis of the latest research, it must be assumed that not 8,000, as we reported yesterday, but 10 to 11,000 passengers were on board. Only 932 were saved. Of which 658 were members of the Kriegsmarine. Serious accusations are now being raised against the Danzig Party offices, who insisted that the "Wilhelm Gustloff" should depart on January 30th, even though the head of the Security Baltic Sea had pointed out that the necessary number of security units could not be placed before February 4.

The "Wilhelm Gustloff" departed nevertheless on the 30th of January in the evening with the completely inadequate securing from an outpost boat and two R-boats. All the decks of the "Wilhelm Gustloff" were so crowded that no one could move. At the embarkation it was said, the journey takes however only a few hours.When the ship was hit by the Russian torpedo at exactly 9 o'clock pm, just an hour after the departure, hardly anybody could escape from the lower decks. Many passengers were thrown into the sea at the time the ship capsized, frozen in the icy water before they could be helped.

Survivors report the horror scene, which took place after the explosion onboard the ship. All lights on board are extinguished at a stroke. In wild panic, the passengers tried to find a way to the deck despite the darkness. Hundreds of women and children were trampled to death on the stairs and corridors.

Women and children

In the fierce battle that took place around the few rescue boats, women and children were ruthlessly pushed overboard. After just ten minutes, the 25,000 - ton ship listed hard. Five minutes later, the "Wilhelm Gustloff" capsized and took many thousands with her into the depth. Others, who had fallen from the deck or hurled into the sea, fell into the wake of the sinking ship and disappeared into the flood. The "Wilhelm Gustloff" was finished in 1937 as a KdF ship and was taken over by the Kriegsmarine in 1940 first as a hospital ship. Since March 1941 she was the home of the submarine teaching division in Gotenhafen.

Party stormed with inquiries

The offices of the Party and the Navy in all parts of the Reich were yesterday stormed by anxious persons, who suspect that their relatives were perhaps onboard the "Wilhelm Gustloff", which was torpedoed by a Russian submarine on January 30th at 9:00 pm in the Danzig Bay and sunk within 15 minutes. The number of victims of the "Wilhelm Gustloff" disaster is still not certain, since no office of the Party or of the Kriegsmarine can accurately say, how many Eastern refugees and members of the Wehrmacht were on board, when the ship left Gotenhafen.

932 saved

On the basis of the latest research, it must be assumed that not 8,000, as we reported yesterday, but 10 to 11,000 passengers were on board. Only 932 were saved. Of which 658 were members of the Kriegsmarine. Serious accusations are now being raised against the Danzig Party offices, who insisted that the "Wilhelm Gustloff" should depart on January 30th, even though the head of the Security Baltic Sea had pointed out that the necessary number of security units could not be placed before February 4.

The "Wilhelm Gustloff" departed nevertheless on the 30th of January in the evening with the completely inadequate securing from an outpost boat and two R-boats. All the decks of the "Wilhelm Gustloff" were so crowded that no one could move. At the embarkation it was said, the journey takes however only a few hours.When the ship was hit by the Russian torpedo at exactly 9 o'clock pm, just an hour after the departure, hardly anybody could escape from the lower decks. Many passengers were thrown into the sea at the time the ship capsized, frozen in the icy water before they could be helped.

Survivors report the horror scene, which took place after the explosion onboard the ship. All lights on board are extinguished at a stroke. In wild panic, the passengers tried to find a way to the deck despite the darkness. Hundreds of women and children were trampled to death on the stairs and corridors.

Women and children

In the fierce battle that took place around the few rescue boats, women and children were ruthlessly pushed overboard. After just ten minutes, the 25,000 - ton ship listed hard. Five minutes later, the "Wilhelm Gustloff" capsized and took many thousands with her into the depth. Others, who had fallen from the deck or hurled into the sea, fell into the wake of the sinking ship and disappeared into the flood. The "Wilhelm Gustloff" was finished in 1937 as a KdF ship and was taken over by the Kriegsmarine in 1940 first as a hospital ship. Since March 1941 she was the home of the submarine teaching division in Gotenhafen.

The current count for the casualities for the Wilhelm Gustloff came from the Discovery Channel's TV documentary Unsolved History: Wilhelm Gustloff World's Deadliest Sea Disaster. A computer simulation of how the passengers reacted was created based on known facts of the sinking and population densities around the stairwells and escape hatches on each deck. Part of this computer generation can be viewed here. The end result was roughly 10,573 people on board - 1,230 Survivors and 9,343 dead.

There are many variations in the number of those thought to have been lost on the Wilhelm Gustloff. Several primary shown below give their accounts from the time. My personal notes and views on this can be read on the last page of the museum website.

There are many variations in the number of those thought to have been lost on the Wilhelm Gustloff. Several primary shown below give their accounts from the time. My personal notes and views on this can be read on the last page of the museum website.

Christian Memory (Rememberance)

of our dear, unforgettable

Son and brother

Marine Corporal

(Heinrich) Heini Maschberger

which on 31 January 1945

at the age of 18 years in the Gulf of Gdansk is mourned in passing in the faithful duty of sailor.

Mother dry your tears!

When I met the wrinkled ore

Was with me in the last chord:

Do not break - not, break your mother's heart!

I'm gone to the death of the hero,

Bear as a heroine this pain.

Do not break - not, break your mother's heart!

of our dear, unforgettable

Son and brother

Marine Corporal

(Heinrich) Heini Maschberger

which on 31 January 1945

at the age of 18 years in the Gulf of Gdansk is mourned in passing in the faithful duty of sailor.

Mother dry your tears!

When I met the wrinkled ore

Was with me in the last chord:

Do not break - not, break your mother's heart!

I'm gone to the death of the hero,

Bear as a heroine this pain.

Do not break - not, break your mother's heart!

Wilhelm Gustloff Death Card from sinking:

Heinrich Maschberger is listed as 'Seemanstod' or 'Seemannstod' as on the card (Accidental death) in the Gulf of Gdansk. He was in all likelihood one of 918 Marines and U-Boat members from 2nd U-Boat Training Division that went down with the Wilhelm Gustloff since no other ships were known to be sunk on the 31st in the Baltic. Dated the day after the sinking.

Heinrich Maschberger is listed as 'Seemanstod' or 'Seemannstod' as on the card (Accidental death) in the Gulf of Gdansk. He was in all likelihood one of 918 Marines and U-Boat members from 2nd U-Boat Training Division that went down with the Wilhelm Gustloff since no other ships were known to be sunk on the 31st in the Baltic. Dated the day after the sinking.

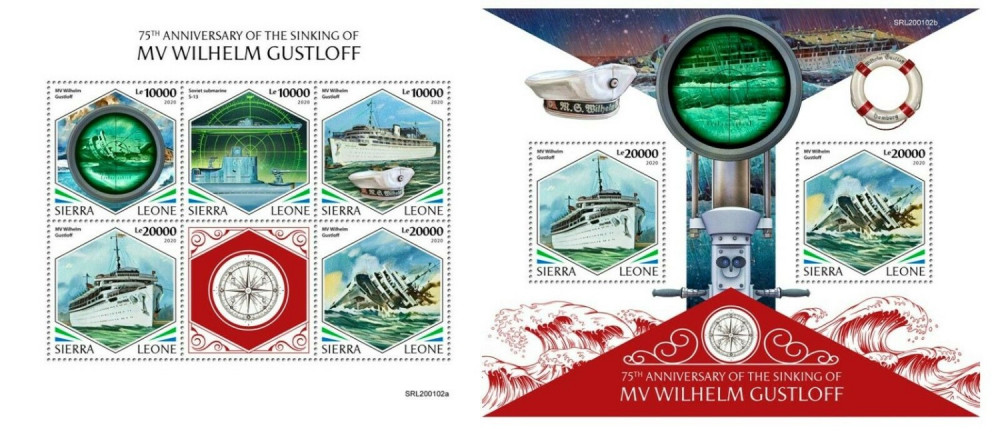

Wilhelm Gustloff Life rings / Life Preservers

Reproduction life rings, most often associated with the sinking of the ship.

Two variations of the life ring were known to have been used on board - the differences lie within the lettering of the ship's name around the top. For one example, the 'ff' in Gustloff can be connected or separated. Shows signs of aging - paint loss around the rope handles, one can tell it has been painted more than once on both sides over the years and repairs have been made to it. Usual cracking and bumps / dents. There are no known original life rings that survived the sinking.

The first red and white life ring is a prop from the 2008 movie "Die Gustloff". The second white life ring is a reproduction created in the style of those used in the Gustloff movies. Below: The first photo of it was ripped off my website to be manipulated and used for the 2020 Sierra Leone 75th Anniversary of the Sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff stamps in Africa. The Donald Duck cap & tally photo was also taken from the souvenir page and used without permission.

Reproduction life rings, most often associated with the sinking of the ship.

Two variations of the life ring were known to have been used on board - the differences lie within the lettering of the ship's name around the top. For one example, the 'ff' in Gustloff can be connected or separated. Shows signs of aging - paint loss around the rope handles, one can tell it has been painted more than once on both sides over the years and repairs have been made to it. Usual cracking and bumps / dents. There are no known original life rings that survived the sinking.

The first red and white life ring is a prop from the 2008 movie "Die Gustloff". The second white life ring is a reproduction created in the style of those used in the Gustloff movies. Below: The first photo of it was ripped off my website to be manipulated and used for the 2020 Sierra Leone 75th Anniversary of the Sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff stamps in Africa. The Donald Duck cap & tally photo was also taken from the souvenir page and used without permission.

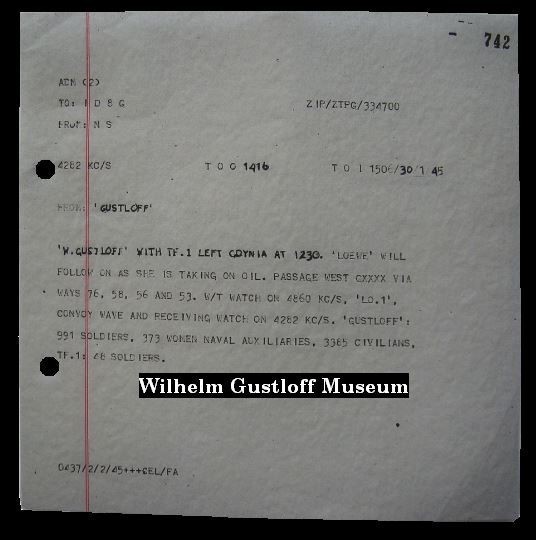

By all historical accounts, the tally of the people which were officially embarked on the Wilhelm Gustloff on 1/30/45 stopped around 5,000. This is a period newspaper clipping with a photograph of the actual list from that fateful day. The tally translates:

Soldaten (Soldiers) 918

**(The 918 soldiers mentioned were all from the 2. U-Boot-Lehrdivision and should have been brought to Kiel to fight on.)

Besatzung (crew) 172

Mar. Helfer (abbreviation for marine volunteer) 373

Verwund (abbreviation for wounded people) 73

---------

1537

Flüchtl (Abb. for refugee) 3121

---------

4658

+2-300 (An additional 200 to 300 / from) Pillau (Village in former Ostpreussen)

Wilh. Gustloff is written in blue pen on the paper. The article at the bottom translates:

"A yellowed slip of shows the number of people carried on the Gustloff: 4,958. This list was handed over by the First officer, Louis Reese, (Photo) shortly before the Gustloff's departure. The number of stowaways was never determined."

A lesser known fact was that the printer aboard the ship, Jeisle, printed some 10,000 meal ticket to be issued to the refugees for food during the voyage. Navy Nurse Waldemar Terres reported that by January 29th at 5pm, 7,956 meal tickets were issued. The additional 2,000 were distributed afterwards, but their count was not kept.

Soldaten (Soldiers) 918

**(The 918 soldiers mentioned were all from the 2. U-Boot-Lehrdivision and should have been brought to Kiel to fight on.)

Besatzung (crew) 172

Mar. Helfer (abbreviation for marine volunteer) 373

Verwund (abbreviation for wounded people) 73

---------

1537

Flüchtl (Abb. for refugee) 3121

---------

4658

+2-300 (An additional 200 to 300 / from) Pillau (Village in former Ostpreussen)

Wilh. Gustloff is written in blue pen on the paper. The article at the bottom translates:

"A yellowed slip of shows the number of people carried on the Gustloff: 4,958. This list was handed over by the First officer, Louis Reese, (Photo) shortly before the Gustloff's departure. The number of stowaways was never determined."

A lesser known fact was that the printer aboard the ship, Jeisle, printed some 10,000 meal ticket to be issued to the refugees for food during the voyage. Navy Nurse Waldemar Terres reported that by January 29th at 5pm, 7,956 meal tickets were issued. The additional 2,000 were distributed afterwards, but their count was not kept.

Gerhard Graßhoff - Survivor of the Wilhelm Gustloff Disaster

These documents were discovered in a large binder of paperwork recently purchased from Germany on the ship. Photos at left of survivor Gerhard Grasshoff and the interview done by Vanessa Philipp and Lisa Schiefner on March 6th, 2008.

"Wilhelm Gustloff" : From the Flagship to the Iron Coffin.

Interview: Gerhard Grasshoff (86):

Gerhard was born in 1922 in Uichteritz

These documents were discovered in a large binder of paperwork recently purchased from Germany on the ship. Photos at left of survivor Gerhard Grasshoff and the interview done by Vanessa Philipp and Lisa Schiefner on March 6th, 2008.

"Wilhelm Gustloff" : From the Flagship to the Iron Coffin.

Interview: Gerhard Grasshoff (86):

Gerhard was born in 1922 in Uichteritz

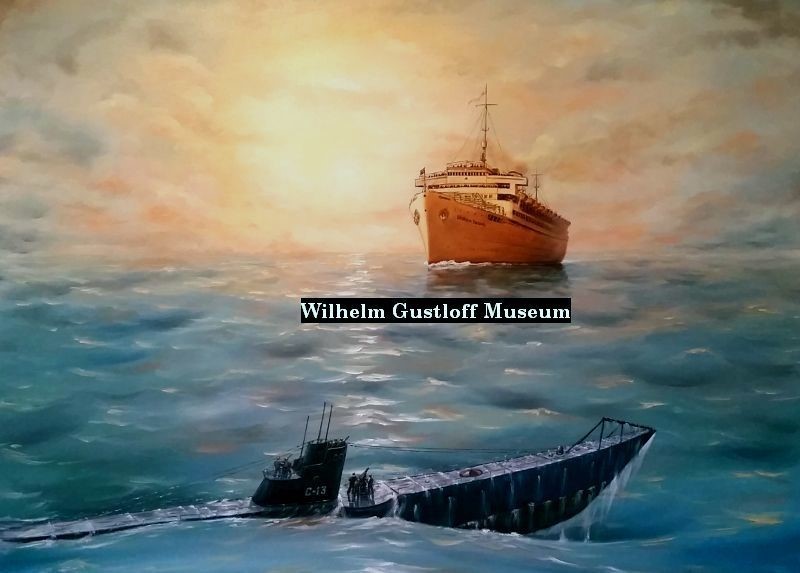

Alexander Ivanovich Marinesko (Russian: Александр Иванович Маринеско) (January 15, 1913 - November 25, 1963) was a Soviet naval officer and during World War II, the captain of the S-13 submarine, which sank the German ship Wilhelm Gustloff, with recent research showing that over 9,000 died when the ship sank.

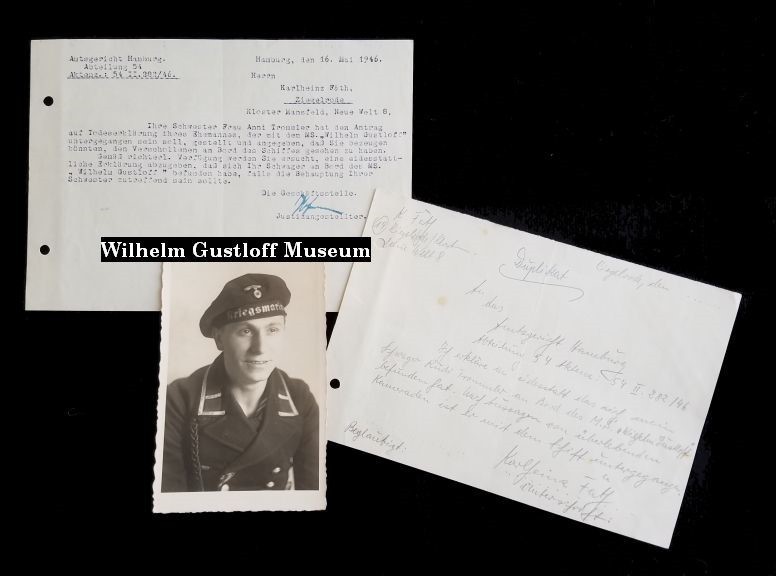

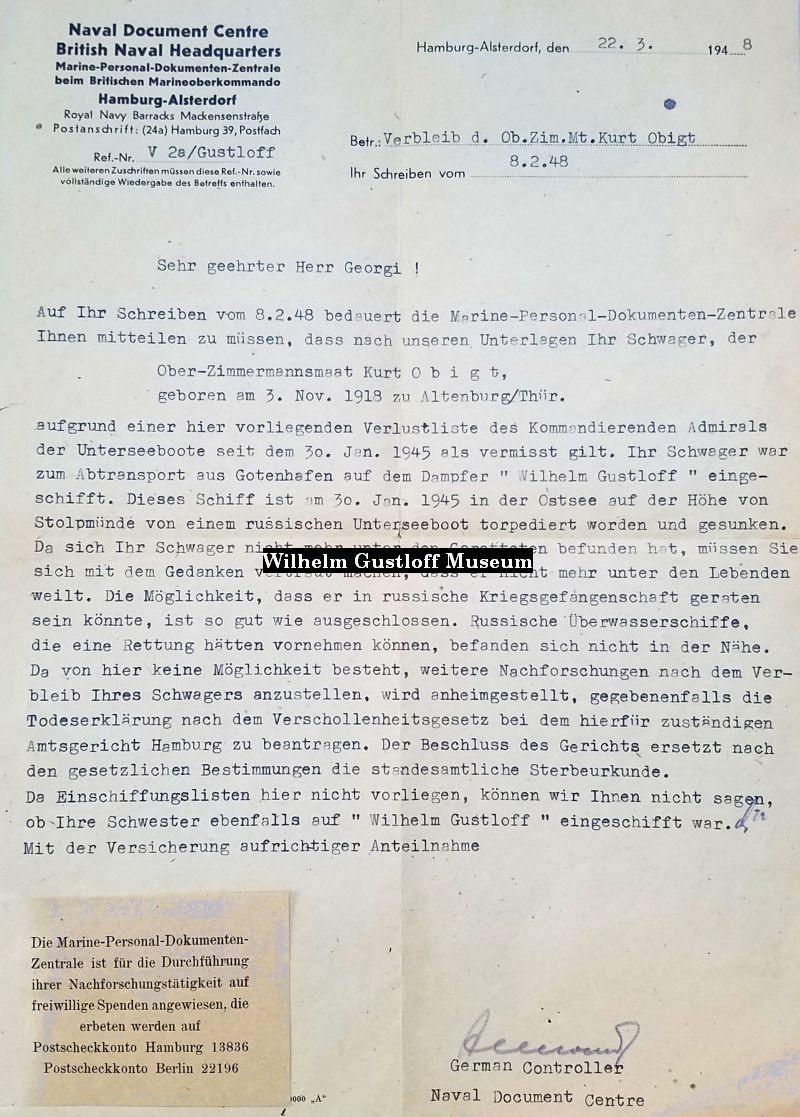

Letter from the Naval Document Centre, British Naval Headquarters

A letter to Mrs. Wiechert that her relative was lost with the Wilhelm Gustloff

English translation at right top

Original German transcription at right below.

A special thank you to Werner Hinke for translating this document for me!

A letter to Mrs. Wiechert that her relative was lost with the Wilhelm Gustloff

English translation at right top

Original German transcription at right below.

A special thank you to Werner Hinke for translating this document for me!

Naval Document Centre (21a) Minden i.W., den November 22nd, 1946.

British Naval Headquarters

Navy - Personnel - Documents - Central

At the British Navy High Command

Ref-Nr. Vd 5806

All further correspondence must include this

Ref. Num. as well as the complete reference.

Re:.San Ensign d.R. Gustav Fehr, ship "Wilhelm Gustloff"

Your letter dated 22.6.1946

Dear Miss Wiechert!

It is with sadness, that we need to make this painful notification. San. Ensign d.R. Gustav Fehr, born on 26.2.1921 in Wuppertal-Barmen, has been listed as "missing " as of the 30.1.1945. The Commanding Admiral of the U-boats has included his name on the list of missing persons on 12.4.45. We have reviewed this list. Some of the members of the 2. U.L.D., among them San Ensign d.R. Gustav Fehr, boarded the former K.d.F.ship "Wilhelm Gustloff". This ship was torpedoed on 31.1.45 by a Russian submarine and sank near Stolpemünde in the Baltic Sea. San Ensign Gustav Fehr was not among the survivors. You must therefore accept the idea that he is no longer among the living. The possibility of him becoming a Russian prisoner is non existent. There were no Russian surface ships in the vicinity. We have no record of soldiers rescued or imprisoned by the Russians.

With the assurance of our sincere sympathy.

German Controller

Naval Document Centre

British Naval Headquarters

Navy - Personnel - Documents - Central

At the British Navy High Command

Ref-Nr. Vd 5806

All further correspondence must include this

Ref. Num. as well as the complete reference.

Re:.San Ensign d.R. Gustav Fehr, ship "Wilhelm Gustloff"

Your letter dated 22.6.1946

Dear Miss Wiechert!

It is with sadness, that we need to make this painful notification. San. Ensign d.R. Gustav Fehr, born on 26.2.1921 in Wuppertal-Barmen, has been listed as "missing " as of the 30.1.1945. The Commanding Admiral of the U-boats has included his name on the list of missing persons on 12.4.45. We have reviewed this list. Some of the members of the 2. U.L.D., among them San Ensign d.R. Gustav Fehr, boarded the former K.d.F.ship "Wilhelm Gustloff". This ship was torpedoed on 31.1.45 by a Russian submarine and sank near Stolpemünde in the Baltic Sea. San Ensign Gustav Fehr was not among the survivors. You must therefore accept the idea that he is no longer among the living. The possibility of him becoming a Russian prisoner is non existent. There were no Russian surface ships in the vicinity. We have no record of soldiers rescued or imprisoned by the Russians.

With the assurance of our sincere sympathy.

German Controller

Naval Document Centre

Naval Document Centre (21a) Minden i.W., den November 22nd, 1946.

British Naval Headquarters

Marine - Personal - Dokumenten - Zentrale

beim Britischen Marineoberkommando

Ref-Nr. Vd 5806

Alle weiteren Zuschriften müssen diese Ref-Nr.

sowie vollständige Wiedergabe des Betreffs enthalten

Betr.: San. Fähnrich d. R. Gustav Fehr, Schiff "Wilhelm Gustloff"

Ihr Schreiben vom 22.6.1946.

Sehr verehrtes Fräulein Wiechert!

Es wird bedauert, Ihnen die schmerzliche Mitteilung machen zu müssen, dass der San. Fähnrich d. R. Gustav Fehr, geb. am 26.2.1921 in Wuppertal-Barmen, auf Grund mandierenden Admirals der Unterseeboote" vom 12.4.1945 seit dem 30.1.1945 als "vermisst" geführt wird. Ein Teil der 2.U.L.D., Gotenhafen, darunter der San. Fähnrich d. früheren K.d.F. - Schiff "Wilhelm Gustloff"eingeschifft. Dieses Schiff ist am 30.1.1945 in der Ostsee auf der Höhe von Stolpmünde von einem russischen Unterseeboot torpediert worden und gesunken. Da sich der San. Fähnrich d.R. Gustav Fehr nicht unter den geretteten befunden hat, müssen Sie sich mit dem gedanken vertraut machen, dass er nicht mehr unter den Lebenden weilt. Die Möglichkeit, dass er in russische Gefangen schaft geraten sein könnte, ist so gut wie ausgeschlossen. Russische Überwassweschiffe, die eine Rettung hätten vornehmen können, befanden sich nicht in der Nähe. Ebenso sind Namen von Geretteten bezw. in Gefangenschaft geratenen Soldaten heir nicht bekannt. Mit der Versicherung aufrichtiger Anteilnahme.

German Controller

Naval Document Centre

British Naval Headquarters

Marine - Personal - Dokumenten - Zentrale

beim Britischen Marineoberkommando

Ref-Nr. Vd 5806

Alle weiteren Zuschriften müssen diese Ref-Nr.

sowie vollständige Wiedergabe des Betreffs enthalten

Betr.: San. Fähnrich d. R. Gustav Fehr, Schiff "Wilhelm Gustloff"

Ihr Schreiben vom 22.6.1946.

Sehr verehrtes Fräulein Wiechert!

Es wird bedauert, Ihnen die schmerzliche Mitteilung machen zu müssen, dass der San. Fähnrich d. R. Gustav Fehr, geb. am 26.2.1921 in Wuppertal-Barmen, auf Grund mandierenden Admirals der Unterseeboote" vom 12.4.1945 seit dem 30.1.1945 als "vermisst" geführt wird. Ein Teil der 2.U.L.D., Gotenhafen, darunter der San. Fähnrich d. früheren K.d.F. - Schiff "Wilhelm Gustloff"eingeschifft. Dieses Schiff ist am 30.1.1945 in der Ostsee auf der Höhe von Stolpmünde von einem russischen Unterseeboot torpediert worden und gesunken. Da sich der San. Fähnrich d.R. Gustav Fehr nicht unter den geretteten befunden hat, müssen Sie sich mit dem gedanken vertraut machen, dass er nicht mehr unter den Lebenden weilt. Die Möglichkeit, dass er in russische Gefangen schaft geraten sein könnte, ist so gut wie ausgeschlossen. Russische Überwassweschiffe, die eine Rettung hätten vornehmen können, befanden sich nicht in der Nähe. Ebenso sind Namen von Geretteten bezw. in Gefangenschaft geratenen Soldaten heir nicht bekannt. Mit der Versicherung aufrichtiger Anteilnahme.

German Controller

Naval Document Centre

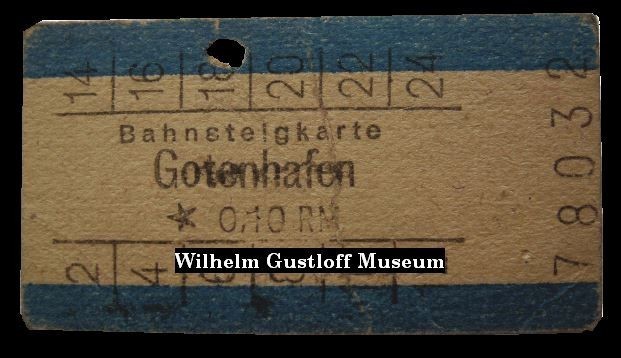

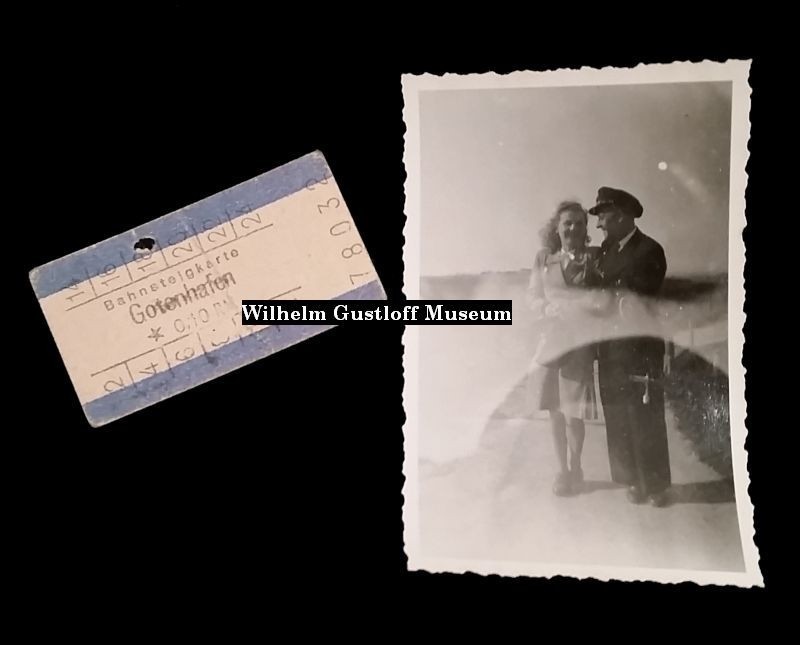

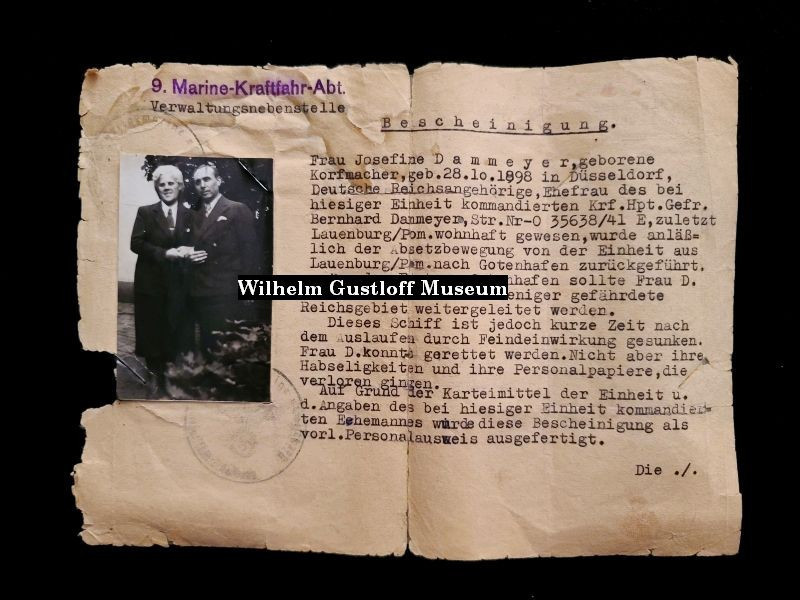

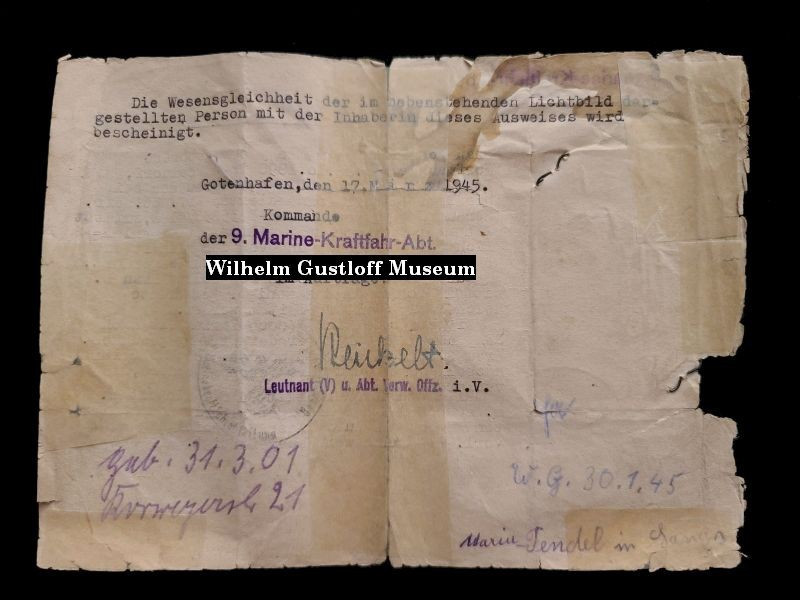

Original Boarding Passes for the Wilhelm Gustloff's Last Voyage

Operation Hannibal - January 30th, 1945.

Of the several hundred boarding passes that were the last thing to be printed from the Gustloff's on board printing press, only 5 are known to still exist. Presented here are two of these five original boarding passes for the Wilhelm Gustloff. Even better is that their story also survived the test of time.

Käthe Kraus, of Adolf Hitler-Strasse 69 in Gotenhafen, was a member of the Kriegsmarine working as a naval aid. In 1945 at the age of 38, she was issued these boarding passes for passage West on the Wilhelm Gustloff. However, due to the amount of 'top secret' paperwork that the Germans were trying to destroy, she recalled how she decided to stay behind to help with the task and take a liner that was leaving at a later date. This saved her life and these extraordinary pieces of history.

After the Wilhelm Gustloff sank, her tasks were finished and she gained passage 2 days later on February 2nd, 1945 on board the H.K.S. Vega leaving Gotenhafen. Her ausweis and 'special pass' from the Vega also survived and are shown below as part of our collection. In her later years living in Kiel, she became friends with her neighbor who was a WWII military collector specializing in minesweepers. Before moving away from Kiel, Mrs. Kraus gave B.W. (military collector name witheld for privacy) these documents for his collection and told him the story I wrote above. In late 2012, I was able to discover that B.W. had these documents still in his collection. After deciding to part with them to 'thin out' non-minesweeper items, I arranged to have them transferred to the Wilhelm Gustloff Museum.

The 1/30/45 ausweis is one of the few items from the Wilhelm Gustloff that are made as official reproductions. I have seen at least one where the bottom was cut off and it was sold as an 'original'. The bottom left has 'Faksimile Edition' (Reproduction Edition); followed by the document number and information. In order to cut off this reproduction giveaway, one would also have to cut off '2. Unterseebootslehrdivision' to get a clean straight cut. I also have one of these reproductions in the collection.

Operation Hannibal - January 30th, 1945.

Of the several hundred boarding passes that were the last thing to be printed from the Gustloff's on board printing press, only 5 are known to still exist. Presented here are two of these five original boarding passes for the Wilhelm Gustloff. Even better is that their story also survived the test of time.

Käthe Kraus, of Adolf Hitler-Strasse 69 in Gotenhafen, was a member of the Kriegsmarine working as a naval aid. In 1945 at the age of 38, she was issued these boarding passes for passage West on the Wilhelm Gustloff. However, due to the amount of 'top secret' paperwork that the Germans were trying to destroy, she recalled how she decided to stay behind to help with the task and take a liner that was leaving at a later date. This saved her life and these extraordinary pieces of history.

After the Wilhelm Gustloff sank, her tasks were finished and she gained passage 2 days later on February 2nd, 1945 on board the H.K.S. Vega leaving Gotenhafen. Her ausweis and 'special pass' from the Vega also survived and are shown below as part of our collection. In her later years living in Kiel, she became friends with her neighbor who was a WWII military collector specializing in minesweepers. Before moving away from Kiel, Mrs. Kraus gave B.W. (military collector name witheld for privacy) these documents for his collection and told him the story I wrote above. In late 2012, I was able to discover that B.W. had these documents still in his collection. After deciding to part with them to 'thin out' non-minesweeper items, I arranged to have them transferred to the Wilhelm Gustloff Museum.

The 1/30/45 ausweis is one of the few items from the Wilhelm Gustloff that are made as official reproductions. I have seen at least one where the bottom was cut off and it was sold as an 'original'. The bottom left has 'Faksimile Edition' (Reproduction Edition); followed by the document number and information. In order to cut off this reproduction giveaway, one would also have to cut off '2. Unterseebootslehrdivision' to get a clean straight cut. I also have one of these reproductions in the collection.

Photo Gallery at right:

1: The two ausweise for the Wilhelm Gustloff. The first for Mrs. Klaus, the second blank. Both stamped.

2: A close-up of Mrs. Klaus' ausweis that never made it back on board the doomed liner.

3: An aerial view of Gotenhafen 12/21/1944. The Wilhelm Gustloff is visible on the left south of the Hansa at the harbor entrance. Her bow is pointing NNE.

4: A color photo of the H.K.S. Vega in Gotenhafen in 1942 with 3 type VIIC-boats and the type IXA boat U-37. In her camouflage paint, this was the ship that Mrs. Kraus escaped Gotenhafen on. There was some issue as to if this ship was renamed the 'Wega' under Kriegsmarine control, but she is clearly the 'Vega' on her ausweis. The liner was later bombed on May 3rd, 1945. To see her history, click HERE.

5: The ausweis for Käthe Kraus on board the H.K.S. Vega.

6: The special pass or 'marching orders for business trip' pass. February 2nd, 1945 for passage to Kiel.

7: Back of the special pass.

8: Signature of the Kriegsmarine Kapitänleutnant (AMD) u. Adjutant.

1: The two ausweise for the Wilhelm Gustloff. The first for Mrs. Klaus, the second blank. Both stamped.

2: A close-up of Mrs. Klaus' ausweis that never made it back on board the doomed liner.

3: An aerial view of Gotenhafen 12/21/1944. The Wilhelm Gustloff is visible on the left south of the Hansa at the harbor entrance. Her bow is pointing NNE.

4: A color photo of the H.K.S. Vega in Gotenhafen in 1942 with 3 type VIIC-boats and the type IXA boat U-37. In her camouflage paint, this was the ship that Mrs. Kraus escaped Gotenhafen on. There was some issue as to if this ship was renamed the 'Wega' under Kriegsmarine control, but she is clearly the 'Vega' on her ausweis. The liner was later bombed on May 3rd, 1945. To see her history, click HERE.

5: The ausweis for Käthe Kraus on board the H.K.S. Vega.

6: The special pass or 'marching orders for business trip' pass. February 2nd, 1945 for passage to Kiel.

7: Back of the special pass.

8: Signature of the Kriegsmarine Kapitänleutnant (AMD) u. Adjutant.

Wilhelm Gustloff Ausweis:

Deutsch schreiben!

Ausweis für MS. "Wilhelm Gustloff"

Name: Käthe Kraus

Bisherige Wohnung: Gotenhafen, Adolf Hitler-Strasse 69

Anschrift der nächsten Angehörigen: Albert Kraus, Butenschönsredder, Flintbek bei Kiel

Kommando

2. Unterseebootslehrdivision

German post!

Pass for MS. "Wilhelm Gustloff"

Name: Käthe Kraus

Previous residence: Gotenhafen, Adolf Hitler-Strasse 69

Address of next of kin: (Yet to be translated)

Command

Second Submarine Training Division

Deutsch schreiben!

Ausweis für MS. "Wilhelm Gustloff"

Name: Käthe Kraus

Bisherige Wohnung: Gotenhafen, Adolf Hitler-Strasse 69

Anschrift der nächsten Angehörigen: Albert Kraus, Butenschönsredder, Flintbek bei Kiel

Kommando

2. Unterseebootslehrdivision

German post!

Pass for MS. "Wilhelm Gustloff"

Name: Käthe Kraus

Previous residence: Gotenhafen, Adolf Hitler-Strasse 69

Address of next of kin: (Yet to be translated)

Command

Second Submarine Training Division

Ausweis Nr. 333 für H.K.S. Vega

Herr/Frau Erl. / Kind (Name) (Vorname) - Käthe Kraus

Alter: 38

Bisherige Vohnung: Gotenhafen, Adolf Hitler-Straße 69

Anschrift der näch-sten Angehörigen: Albert Kraus, Butenschönsredder in Flintbek bei Kiel

Inhaber dieses Ausweises ist berechtigt, das Kriegshafengelände zwecks Einschiffung auf H.K.S. "Vega" zu betreten.

Kommando H.K.S. "Vega"

Verpflegungskarte: Datum morg. / mitt. / abds.

ID No. 333 for H.K.S. Vega

Mr / Ms

Erl / child (name) (first name) - Käthe Kraus

Age: 38

Existing Vohnung: Gdynia, Adolf Hitler-Strasse 69

Address of the next few members:

Holder of this certificate is entitled to the port area for the purpose of embarking on war HKS "Vega" to enter.

Command H.K.S. "Vega"

Catering Menu: Date morg. / Mitt. / Abds

Herr/Frau Erl. / Kind (Name) (Vorname) - Käthe Kraus

Alter: 38

Bisherige Vohnung: Gotenhafen, Adolf Hitler-Straße 69

Anschrift der näch-sten Angehörigen: Albert Kraus, Butenschönsredder in Flintbek bei Kiel

Inhaber dieses Ausweises ist berechtigt, das Kriegshafengelände zwecks Einschiffung auf H.K.S. "Vega" zu betreten.

Kommando H.K.S. "Vega"

Verpflegungskarte: Datum morg. / mitt. / abds.

ID No. 333 for H.K.S. Vega

Mr / Ms

Erl / child (name) (first name) - Käthe Kraus

Age: 38

Existing Vohnung: Gdynia, Adolf Hitler-Strasse 69

Address of the next few members:

Holder of this certificate is entitled to the port area for the purpose of embarking on war HKS "Vega" to enter.

Command H.K.S. "Vega"

Catering Menu: Date morg. / Mitt. / Abds

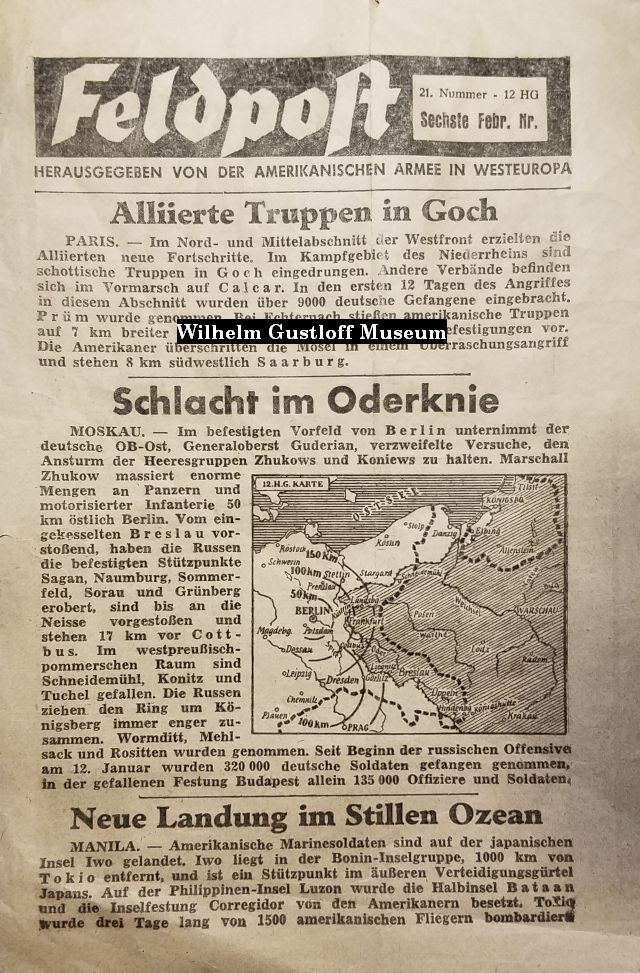

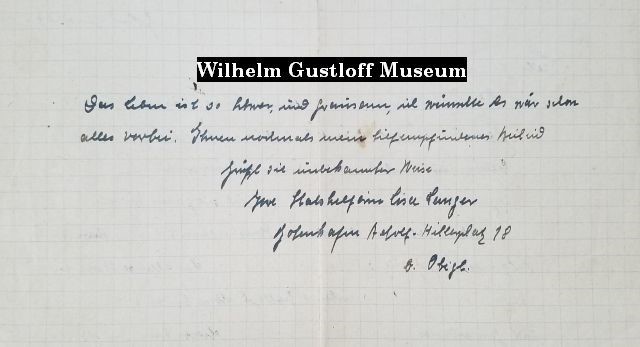

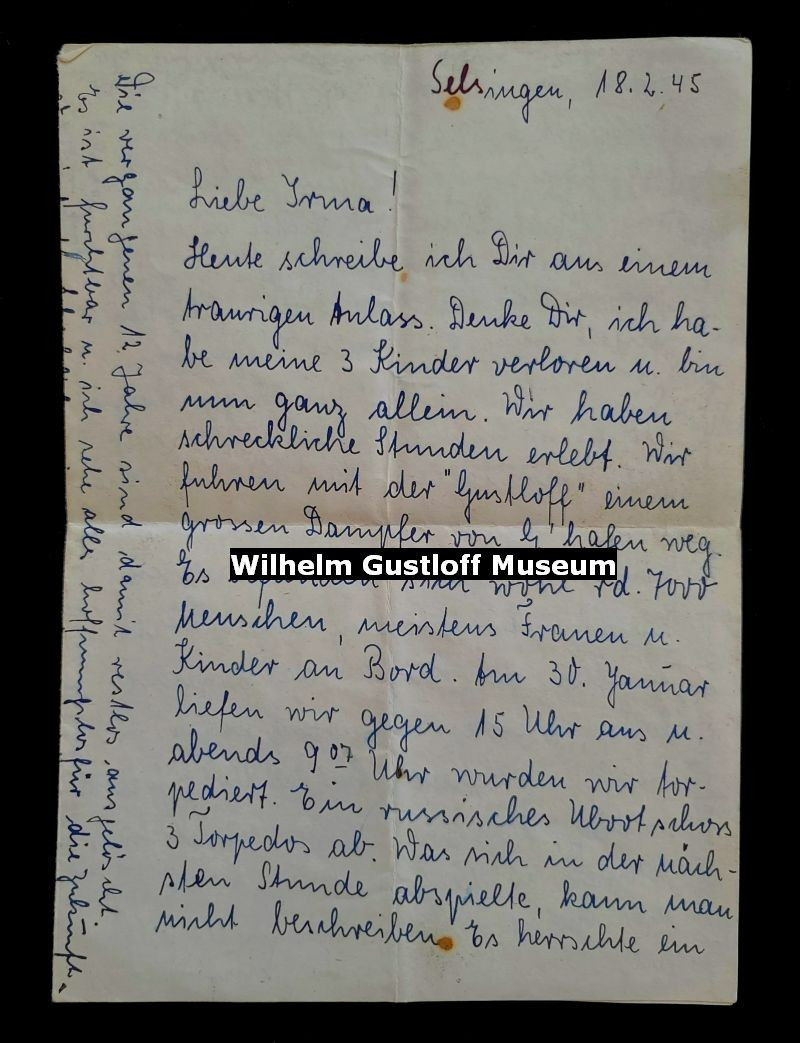

Letter written by a sailor fleeing Gotenhafen - 26.2.1945

Written by Sali Gedig to Adolf Stolz

Sali was on board another ship fleeing the port of Gotenhafen under heavy escort with 14,000 on board! He mentions the Gustloff sinking in his letter to portray the fears of having so many on a single ship....

"Wir hatten ein starkes Geleit mit. Es waren 14000 Menschen oben. Kannst Dir ja den Kasten vorstellen. Vor uns war die Gustloff untergegangen da waren oben 8000 Menschen. Kannst Dir unsere Stimmung vorstellen."

"We had a strong escort with us, 14,000 people were on the decks, so you can imagine the size of the ship. The Gustloff had gone down before us and they had 8,000 people on the top (decks). Imagine our mood."

A special thank you to Werner Hinke for translating this for me.

Written by Sali Gedig to Adolf Stolz

Sali was on board another ship fleeing the port of Gotenhafen under heavy escort with 14,000 on board! He mentions the Gustloff sinking in his letter to portray the fears of having so many on a single ship....

"Wir hatten ein starkes Geleit mit. Es waren 14000 Menschen oben. Kannst Dir ja den Kasten vorstellen. Vor uns war die Gustloff untergegangen da waren oben 8000 Menschen. Kannst Dir unsere Stimmung vorstellen."

"We had a strong escort with us, 14,000 people were on the decks, so you can imagine the size of the ship. The Gustloff had gone down before us and they had 8,000 people on the top (decks). Imagine our mood."

A special thank you to Werner Hinke for translating this for me.

Letter written by Wilhelm Gustloff survivor Egon Jelsen - Civilian crew member.

Written from his hospital bed in Köslin - February 4th, 1945.

Translated by Werner Hinke.

*The first note is that Egon probably refers to being on board the Minensuchboot M375 or Minensuchboot M341 while being rescued.

*It is also interesting how Egon writes that the Wilhelm Gustloff is still in her Red Cross livery, when she has been painted her war gray for the past 4 years. However, recalling details can always be inaccurate or subjective in the shock of such an event. It has been said that many in Germany from the time up to today still believe today the ship set sail in her hospital livery.

Dear Rhoda,

Now we can thank God, I am safe. I wrote to you on January 20th from Gotenhafen that we intended to ship ourselves in on the Wilhelm Gustloff. We did this but in the same night, the ship was torpedoed by an enemy submarine. What happened then was hell in itself. I can hardly remember how I got into a lifeboat and then onto a fast PT boat. There were 40 on this boat taken to the nearest harbor and from there we went to a hospital in Köslin. I remember the Wilhelm Gustloff was overcrowded, the whole deck was occupied with people and when the ship went down, most of them must have drowned in the icy water. How many is anyone's guess. There are 70 survivors here in Köslin, most with frostbites and related things. The Wilhelm Gustloff was a hospital ship and marked as such, sure, there were also wounded soldiers onboard but nobody I have seen with any sort of arms. I cannot say yet whether Lina was rescued - nobody has shown us a passenger list yet.

What will happen now? I want to get out of here as fast as possible and go to Stettin. Right now that is impossible as there is a travel restriction on all passengers. Why?? I think the world should know what a cowardly deed it was to sink a marked Red Cross ship with thousands of women and children. This sort of thing should be made known and not kept secret. I just don't know whether I will ever find my way around in this world. I will try and forget, and when I get to Stettin, I will try to write again. Meanwhile I am here and I don't even own the gown I wear, but I thank God I am alive. I hope for the best. Uncle Egon.

Written from his hospital bed in Köslin - February 4th, 1945.

Translated by Werner Hinke.

*The first note is that Egon probably refers to being on board the Minensuchboot M375 or Minensuchboot M341 while being rescued.

*It is also interesting how Egon writes that the Wilhelm Gustloff is still in her Red Cross livery, when she has been painted her war gray for the past 4 years. However, recalling details can always be inaccurate or subjective in the shock of such an event. It has been said that many in Germany from the time up to today still believe today the ship set sail in her hospital livery.

Dear Rhoda,

Now we can thank God, I am safe. I wrote to you on January 20th from Gotenhafen that we intended to ship ourselves in on the Wilhelm Gustloff. We did this but in the same night, the ship was torpedoed by an enemy submarine. What happened then was hell in itself. I can hardly remember how I got into a lifeboat and then onto a fast PT boat. There were 40 on this boat taken to the nearest harbor and from there we went to a hospital in Köslin. I remember the Wilhelm Gustloff was overcrowded, the whole deck was occupied with people and when the ship went down, most of them must have drowned in the icy water. How many is anyone's guess. There are 70 survivors here in Köslin, most with frostbites and related things. The Wilhelm Gustloff was a hospital ship and marked as such, sure, there were also wounded soldiers onboard but nobody I have seen with any sort of arms. I cannot say yet whether Lina was rescued - nobody has shown us a passenger list yet.

What will happen now? I want to get out of here as fast as possible and go to Stettin. Right now that is impossible as there is a travel restriction on all passengers. Why?? I think the world should know what a cowardly deed it was to sink a marked Red Cross ship with thousands of women and children. This sort of thing should be made known and not kept secret. I just don't know whether I will ever find my way around in this world. I will try and forget, and when I get to Stettin, I will try to write again. Meanwhile I am here and I don't even own the gown I wear, but I thank God I am alive. I hope for the best. Uncle Egon.

Wilhelm

Gustloff Wreck Keys

I purchased this from a well-known nautical collector in Germany who specializes in selling HAPAG memorabilia. In addition to the many other German nautical pieces he sells, I purchased two of these keys off of him. An identical key to these sold on March 22nd, 2014 among the 300 lots at the Atlantic Crossing Auctions in Southampton, England:

Lot 109 Wilhelm Gustloff, A ships key approx. 4 inches long with looped pinch grip handle and circular engineered barrel. Steel manufacture and tempered at one time. The key was recovered from the wreck of the Gustloff on a salvage dive c 1994 forty nine years after her sinking and is in fine condition with obvious salt water marks. Good (Shown at right with the red background from the auction catalog.)

These were originally purchased in Wismar in 1994 along with 2 other keys and 2 spoons from the wreck of the Wilhelm Gustloff. The seller also told me he had the opportunity to purchase a porthole from the Wilhelm Gustloff by the diver, but could not afford it at the time. How I wish I could've purchased that for the museum collection! The last photo is from a period Arbeitertum showing the same keys and locks they belonged to.

I purchased this from a well-known nautical collector in Germany who specializes in selling HAPAG memorabilia. In addition to the many other German nautical pieces he sells, I purchased two of these keys off of him. An identical key to these sold on March 22nd, 2014 among the 300 lots at the Atlantic Crossing Auctions in Southampton, England:

Lot 109 Wilhelm Gustloff, A ships key approx. 4 inches long with looped pinch grip handle and circular engineered barrel. Steel manufacture and tempered at one time. The key was recovered from the wreck of the Gustloff on a salvage dive c 1994 forty nine years after her sinking and is in fine condition with obvious salt water marks. Good (Shown at right with the red background from the auction catalog.)

These were originally purchased in Wismar in 1994 along with 2 other keys and 2 spoons from the wreck of the Wilhelm Gustloff. The seller also told me he had the opportunity to purchase a porthole from the Wilhelm Gustloff by the diver, but could not afford it at the time. How I wish I could've purchased that for the museum collection! The last photo is from a period Arbeitertum showing the same keys and locks they belonged to.

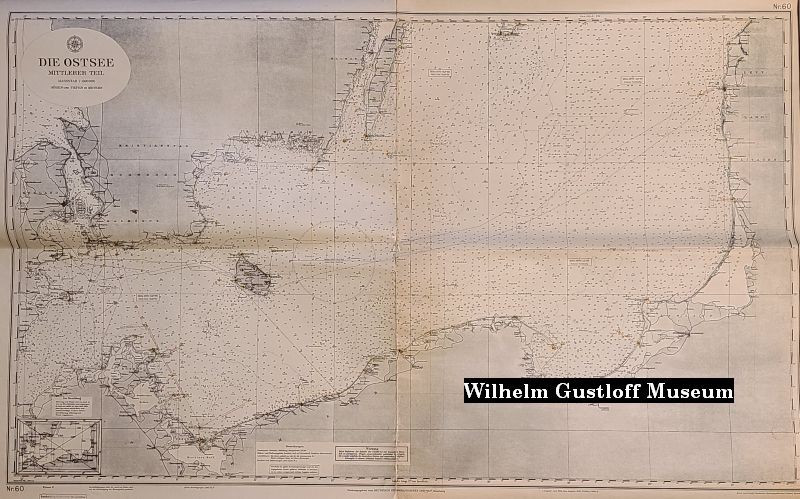

Sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff - January 30th, 1945

List of dead, missing, and survivors by Heinz Schön

Much of the information we know today from the Wilhelm Gustloff is through the efforts of Heinz Schön, who was on board the Wilhelm Gustloff and survived her sinking. Interviewing witnesses and survivors, he began the Gustloff Archive and in 1952 published "The Sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff".

Very few people realize that through his efforts, there is an incomplete list of those who were missing, died, and survived the sinking that night. While published in his works in Germany, I wanted to share his lists here for those who are seeking information on loved ones or family that were on board that fateful night. Heinz died on April 7th, 2013 and his ashes were laid to rest on the wreck on May 10th.

List of dead, missing, and survivors by Heinz Schön

Much of the information we know today from the Wilhelm Gustloff is through the efforts of Heinz Schön, who was on board the Wilhelm Gustloff and survived her sinking. Interviewing witnesses and survivors, he began the Gustloff Archive and in 1952 published "The Sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff".

Very few people realize that through his efforts, there is an incomplete list of those who were missing, died, and survived the sinking that night. While published in his works in Germany, I wanted to share his lists here for those who are seeking information on loved ones or family that were on board that fateful night. Heinz died on April 7th, 2013 and his ashes were laid to rest on the wreck on May 10th.

Wilhelm Gustloff Death Card from sinking #2:

Jesus! † Maria! † Joseph!

Be ready because you do not know the day nor the hour when the Lord will come†

To the pious memory of our dear

Gertrud Schmitt born Herings

which sank on the 30th of January 1945, at ten o'clock pm, with the Wilhelm Gustloff

just before Collberg

The dear deceased was born on March 21, 1921,

and married on the March 27th, 1943 with Hans Schmitt to a happy marriage.

She had a loving heart especially for the poor,

so we hope that she has found a gracious judge above.

Their mourning relatives ask for a prayer for the dear deceased

so that she may soon rest in eternal peace.

Jesus! † Maria! † Joseph!

Be ready because you do not know the day nor the hour when the Lord will come†

To the pious memory of our dear

Gertrud Schmitt born Herings

which sank on the 30th of January 1945, at ten o'clock pm, with the Wilhelm Gustloff

just before Collberg

The dear deceased was born on March 21, 1921,

and married on the March 27th, 1943 with Hans Schmitt to a happy marriage.

She had a loving heart especially for the poor,

so we hope that she has found a gracious judge above.

Their mourning relatives ask for a prayer for the dear deceased

so that she may soon rest in eternal peace.

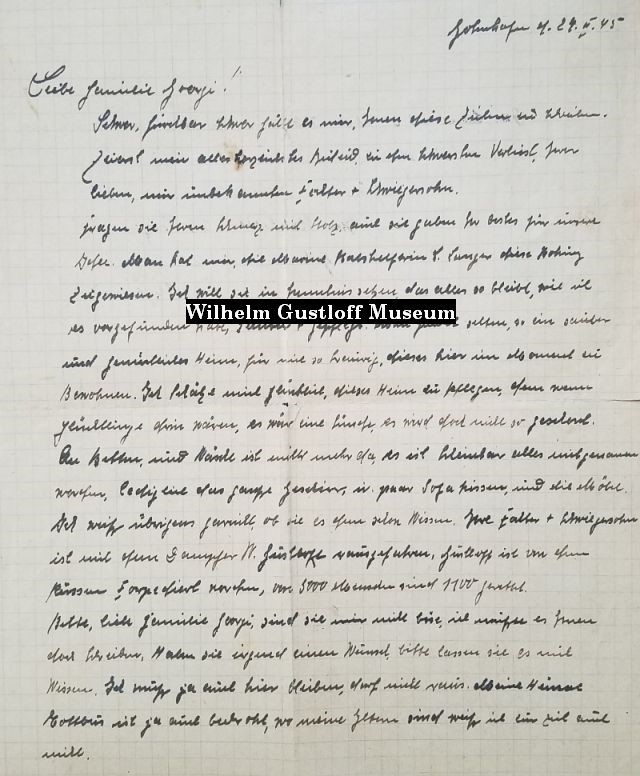

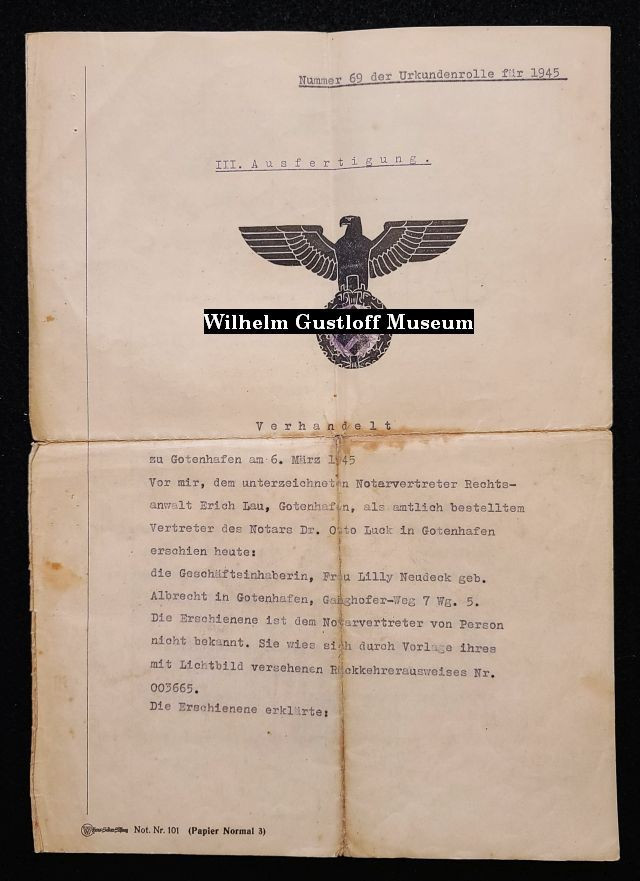

Loan Agreement (Leihvertrag) from July 5th, 1946.

*Thanks to Werner Hinke for translating as always! Excerpts from the letter below:

"We the above named hereby set down the following 'rent' contract. Ms. Anna Wirkner hands over to Ms. Else Wartisch the following things, used, that belonged to the step daughter Gerda Wirkner missing since the sinking of the ship Gustloff.

1 Dining room (giving an inventory)

1 Bedroom ( giving an inventory) ...."

At the end of the letter:

"In the case of the accidental sinking I take the responsibility (liability) for the furniture."

Signed by Else Wartisch and Ernst Wartisch

*Thanks to Werner Hinke for translating as always! Excerpts from the letter below:

"We the above named hereby set down the following 'rent' contract. Ms. Anna Wirkner hands over to Ms. Else Wartisch the following things, used, that belonged to the step daughter Gerda Wirkner missing since the sinking of the ship Gustloff.

1 Dining room (giving an inventory)

1 Bedroom ( giving an inventory) ...."

At the end of the letter:

"In the case of the accidental sinking I take the responsibility (liability) for the furniture."

Signed by Else Wartisch and Ernst Wartisch

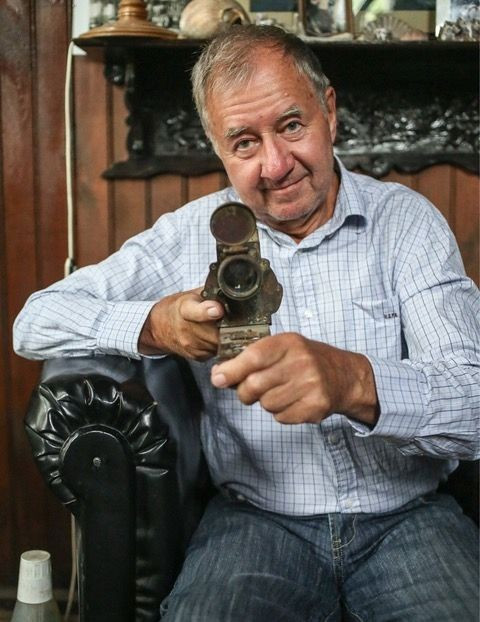

"Radio Room" door plaque from Alexander Marinesko's S-13 Submarine

I came across this piece online from a military collector in Latvia in 2016. Among the other WWII items he was selling, he had this listed as the radio room sign from the Soviet submarine S-13. I had tried to do some research on the S-13, but I was unable to find any information about her scrapping other than her stricken date of 12/17/1956. Since the price wasn't too high, I decided to go for it since he was able to provide a handwritten story to accompany the piece:

"The plaque came from Liepajas Tosmares shipyard territory, where according to the legend was cut into metal Marinesko's S-13 submarine. Liepajas Tosmares shipyard was a closed military area in Soviet times and was part of the Baltic naval war with the code name 29CP3. I got the plaque from workers of Tosmares shipyard about a year ago. Best regards from Liapaja, Latvia."

I came across this piece online from a military collector in Latvia in 2016. Among the other WWII items he was selling, he had this listed as the radio room sign from the Soviet submarine S-13. I had tried to do some research on the S-13, but I was unable to find any information about her scrapping other than her stricken date of 12/17/1956. Since the price wasn't too high, I decided to go for it since he was able to provide a handwritten story to accompany the piece:

"The plaque came from Liepajas Tosmares shipyard territory, where according to the legend was cut into metal Marinesko's S-13 submarine. Liepajas Tosmares shipyard was a closed military area in Soviet times and was part of the Baltic naval war with the code name 29CP3. I got the plaque from workers of Tosmares shipyard about a year ago. Best regards from Liapaja, Latvia."

It provides a great historical piece from the other side of the Wilhelm Gustloff story. If it could speak, what conversations did it hear as Marinesko killed thousands of people onboard the once great passenger liner?

Wooden Deck Plank from the Wilhelm Gustloff Wreck

As the Soviet troops inched closer to Gotenhafen, some of the last evacuees arrived to board the Wilhelm Gustloff. Waltraud Grüter was one of those on board celebrating her 21st birthday. A member of the Marinehelfern or Women’s Naval Auxiliary, Waltraud boarded with her friend Waltraud Idselis and 371 of her comrades a few hours before the ship left port. Due to the lack of room on board, all of the girls were placed down on E Deck in the Gustloff's drained swimming pool surrounded by elaborate tile mosaics.

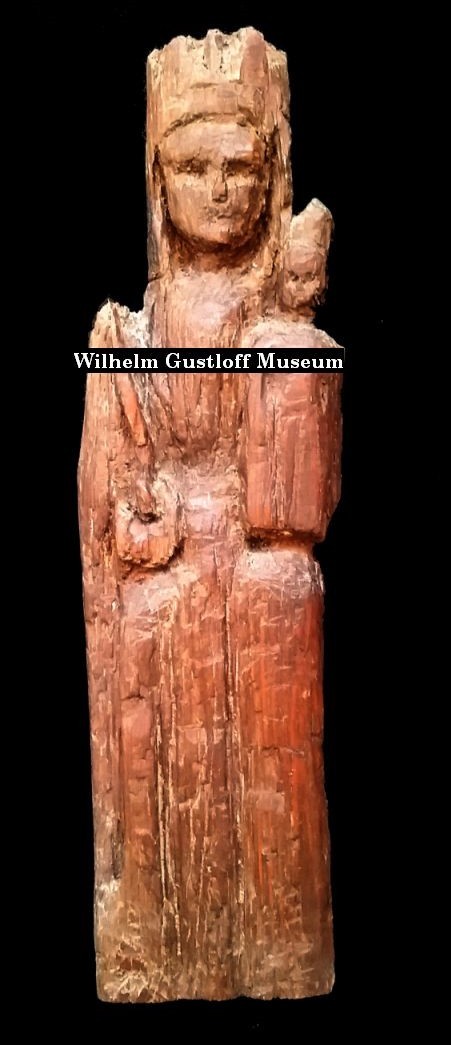

After the Wilhelm Gustloff sank on January 30th, 1945, debris began washing up along the coastlines closest to where the liner went down. On February 11th, 1945, someone discovered some of her debris washed up along the coastal town of Leba, Poland, roughly 50 miles SE of the wrecksite. This included a piece of her deck plank measuring 17”x5”x1” which was picked up off the beach and carved into a figure of the Madonna by an unknown person. Three years later on January 30th, 1948, the piece was presented to Waltraud Grüter to which she typed a note and placed it on the back of the wood:

In grateful memory of our meeting with my lifesavers

Mr. Heinz Schulz and Captain Freidrich Segelken.

The heroes of the night of January 31st, 1945.

The piece from the wreck which was transformed into a Madonna

Will now accompany me into my continued life

For which I express my thanks a thousand times.

Waltraud Grüter, Hamburg, January 30th, 1948.

The wood carving also came with her original Deutsche Rotes Kreuz, Helferin (German Red Cross Assistant) badge that was attached to her uniform the night of the sinking and survived with her.

After acquiring this piece, I wrote to a newspaper reporter, Christian Harborth, in Germany who interviewed Waltraud about the sinking for the online newspaper Hildesheimer Allgemeine Zeitung back in 2011. He was able to go visit Waltraud on my behalf where she is now 92 years old and suffering from dementia in a nursing home on January 27th, 2016. He wrote back to me: “I visited her yesterday, but she did not recognize me. I also showed her your photos, when Madonna she said 'Das bin ich‘, 'This is me' - meaning that they once belonged to her, (mine).“ In an effort to assist in finding out more, Christian ran a front page article in the newspaper on January 30th, 2016 in the hopes that someone out there may know more about the Madonna (possibly who carved it) and be able to give a greater voice to its story.

A special thanks to Werner Hinke for translating the back of this for me.

After the Wilhelm Gustloff sank on January 30th, 1945, debris began washing up along the coastlines closest to where the liner went down. On February 11th, 1945, someone discovered some of her debris washed up along the coastal town of Leba, Poland, roughly 50 miles SE of the wrecksite. This included a piece of her deck plank measuring 17”x5”x1” which was picked up off the beach and carved into a figure of the Madonna by an unknown person. Three years later on January 30th, 1948, the piece was presented to Waltraud Grüter to which she typed a note and placed it on the back of the wood:

In grateful memory of our meeting with my lifesavers

Mr. Heinz Schulz and Captain Freidrich Segelken.

The heroes of the night of January 31st, 1945.

The piece from the wreck which was transformed into a Madonna

Will now accompany me into my continued life

For which I express my thanks a thousand times.

Waltraud Grüter, Hamburg, January 30th, 1948.

The wood carving also came with her original Deutsche Rotes Kreuz, Helferin (German Red Cross Assistant) badge that was attached to her uniform the night of the sinking and survived with her.

After acquiring this piece, I wrote to a newspaper reporter, Christian Harborth, in Germany who interviewed Waltraud about the sinking for the online newspaper Hildesheimer Allgemeine Zeitung back in 2011. He was able to go visit Waltraud on my behalf where she is now 92 years old and suffering from dementia in a nursing home on January 27th, 2016. He wrote back to me: “I visited her yesterday, but she did not recognize me. I also showed her your photos, when Madonna she said 'Das bin ich‘, 'This is me' - meaning that they once belonged to her, (mine).“ In an effort to assist in finding out more, Christian ran a front page article in the newspaper on January 30th, 2016 in the hopes that someone out there may know more about the Madonna (possibly who carved it) and be able to give a greater voice to its story.

A special thanks to Werner Hinke for translating the back of this for me.

#1: Front of carving.

#2: Back of carving.

#3: Note on back.

#4: Location found - Fundort: Leba.

#5: Map of the wreck and Leba.

#6: Waltraud's Red Cross pin worn the night of the sinking.

#7: Photo from Christian Harborth of Waltraud Grüter holding a photo of her friend Waltraud Idselis and her boyfriend in 1944. Used in the 2011 article "I Want to Live" detailing her escape from the Wilhelm Gustloff.

#8: Online article regarding the Madonna carving in 2016.

#2: Back of carving.

#3: Note on back.

#4: Location found - Fundort: Leba.

#5: Map of the wreck and Leba.

#6: Waltraud's Red Cross pin worn the night of the sinking.

#7: Photo from Christian Harborth of Waltraud Grüter holding a photo of her friend Waltraud Idselis and her boyfriend in 1944. Used in the 2011 article "I Want to Live" detailing her escape from the Wilhelm Gustloff.

#8: Online article regarding the Madonna carving in 2016.

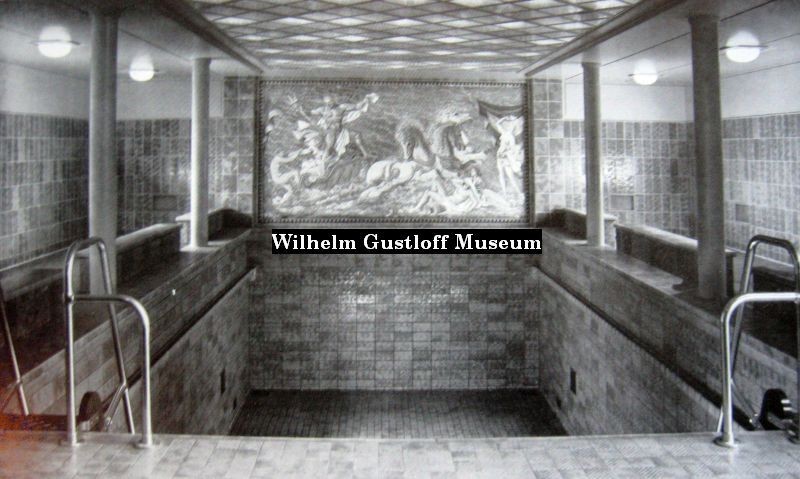

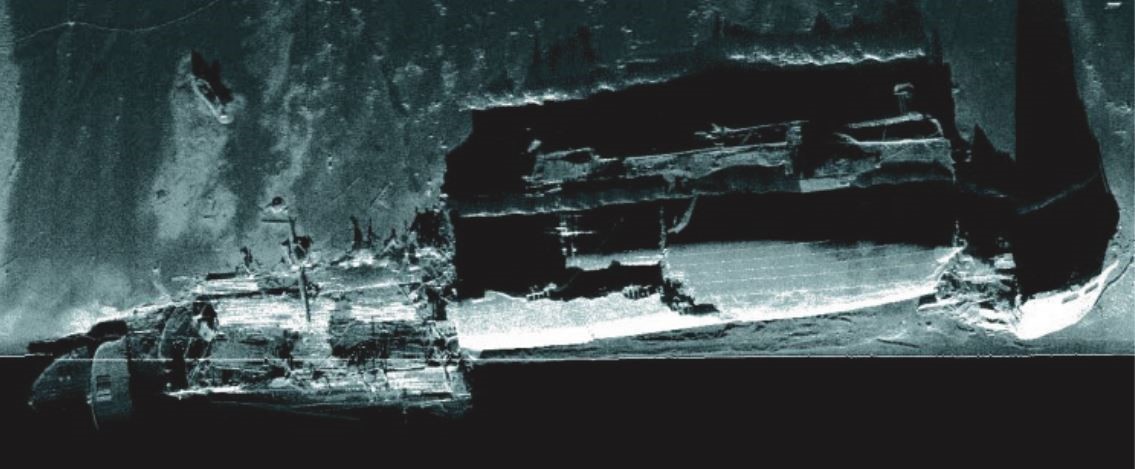

Mosaic Tile from the Wilhelm Gustloff's Swimming Pool

When the Wilhelm Gustloff set sail on January 30th, 1945, among those who were "lucky" enough to gain passage on board were 373 Marine Helferin or Women's Naval Auxiliary. Their accommodations were the Gustloff's drained swimming pool located in the forward section of E Deck. For a passenger liner that was built for simplicity and comfort, her swimming pool was lavishly tiled with a large mosaic of Neptune riding on a shell being pulled by horses from the sea. Just a few years prior, passengers gathered here to relax and play games during her many voyages. Since WWII began, her pool had been drained and now it was considered a safe place to be as the liner was fleeing the Russians.

Then the S-13 took up her position on the Wilhelm Gustloff's port side and fired three torpedoes at the liner. The first torpedo hit at the bow, but the second found its mark at the swimming pool. The casual conversation and banter between the women soon erupted into screams of chaos and agony. The explosion rocked the swimming pool and surrounding locker rooms shattering the tiles and turning them into flying knives. Metal, concrete, and timbers flew into the pool as the glass ceiling shattered and pierced the women below. Water rushed in drowning them within seconds as they never had a chance to escape. Only two or three are known to have escaped the pool and the ship that night.

I have become friends with several well-known divers over the years, and one of them recently contacted me about a piece he had sitting in the darkness of his basement for many years and thought it deserved a new home. During one of his dives on the wreck, he was floating over the area between the bow and severed hull. This debris field was created when the explosives used to collapse the wreck went off, ripping through the bridge, Smoking Lounge, crew's quarters, and the swimming pool. The contents of these rooms spilled out onto the Baltic Sea floor. He recalled how he could look into the wreck "as if it were a 3 story building that had just collapsed." He then saw what looked like a brick sticking out of the mud. He grabbed it, realizing it was a heavier piece. Still unable to see what it was, he pushed off some of the mud to reveal some tile. Once the tile was revealed, he decided to raise it to the surface. After attaching lifting balloons, the large piece of the Wilhelm Gustloff began its ascent to the surface. Soon, it saw light for the first time since 1945. After his crew helped him lift it onto the boat, he poured nothing but seawater on the piece.

With his diving buddies standing around him, it was revealed that this is the only known piece of the Neptune mosaic from the Wilhelm Gustloff's swimming pool ever recovered! Weighing in at 35lbs, it measures 18"x14"x5" at the highest spot. He was looking for a better home since it sat in his basement since he recovered it. I am more than thrilled that he elected to see the piece come into the museum collection where it now stands as the centerpiece of the collection.

I have spent several hours trying to locate where exactly this piece came from on the mosaic. With the assistance of my followers online, the section was discovered and outlined in red in a photo on the right. The color images shown are of a 1:5 scale model from the movie Die Gustloff with the Marine Helferin inserted through CGI, but the mosaic is not accurate. An additional image is one I colorized and overlayed the CGI mosaic on the top. Blohm + Voss was not able to give me more information regarding details of the pool's construction.

Every last piece was saved after the tile was unpacked and cleaned off. Included on the right are the pieces that fell off in transit. 3 vials of rusticles from the Wilhelm Gustloff and a few shards of green tile that were found in the bottom of the wrappings.

Below: The finished pool in March of 1938. The mosaic was made up of around 74,000 individual tiles!

When the Wilhelm Gustloff set sail on January 30th, 1945, among those who were "lucky" enough to gain passage on board were 373 Marine Helferin or Women's Naval Auxiliary. Their accommodations were the Gustloff's drained swimming pool located in the forward section of E Deck. For a passenger liner that was built for simplicity and comfort, her swimming pool was lavishly tiled with a large mosaic of Neptune riding on a shell being pulled by horses from the sea. Just a few years prior, passengers gathered here to relax and play games during her many voyages. Since WWII began, her pool had been drained and now it was considered a safe place to be as the liner was fleeing the Russians.

Then the S-13 took up her position on the Wilhelm Gustloff's port side and fired three torpedoes at the liner. The first torpedo hit at the bow, but the second found its mark at the swimming pool. The casual conversation and banter between the women soon erupted into screams of chaos and agony. The explosion rocked the swimming pool and surrounding locker rooms shattering the tiles and turning them into flying knives. Metal, concrete, and timbers flew into the pool as the glass ceiling shattered and pierced the women below. Water rushed in drowning them within seconds as they never had a chance to escape. Only two or three are known to have escaped the pool and the ship that night.

I have become friends with several well-known divers over the years, and one of them recently contacted me about a piece he had sitting in the darkness of his basement for many years and thought it deserved a new home. During one of his dives on the wreck, he was floating over the area between the bow and severed hull. This debris field was created when the explosives used to collapse the wreck went off, ripping through the bridge, Smoking Lounge, crew's quarters, and the swimming pool. The contents of these rooms spilled out onto the Baltic Sea floor. He recalled how he could look into the wreck "as if it were a 3 story building that had just collapsed." He then saw what looked like a brick sticking out of the mud. He grabbed it, realizing it was a heavier piece. Still unable to see what it was, he pushed off some of the mud to reveal some tile. Once the tile was revealed, he decided to raise it to the surface. After attaching lifting balloons, the large piece of the Wilhelm Gustloff began its ascent to the surface. Soon, it saw light for the first time since 1945. After his crew helped him lift it onto the boat, he poured nothing but seawater on the piece.

With his diving buddies standing around him, it was revealed that this is the only known piece of the Neptune mosaic from the Wilhelm Gustloff's swimming pool ever recovered! Weighing in at 35lbs, it measures 18"x14"x5" at the highest spot. He was looking for a better home since it sat in his basement since he recovered it. I am more than thrilled that he elected to see the piece come into the museum collection where it now stands as the centerpiece of the collection.

I have spent several hours trying to locate where exactly this piece came from on the mosaic. With the assistance of my followers online, the section was discovered and outlined in red in a photo on the right. The color images shown are of a 1:5 scale model from the movie Die Gustloff with the Marine Helferin inserted through CGI, but the mosaic is not accurate. An additional image is one I colorized and overlayed the CGI mosaic on the top. Blohm + Voss was not able to give me more information regarding details of the pool's construction.

Every last piece was saved after the tile was unpacked and cleaned off. Included on the right are the pieces that fell off in transit. 3 vials of rusticles from the Wilhelm Gustloff and a few shards of green tile that were found in the bottom of the wrappings.

Below: The finished pool in March of 1938. The mosaic was made up of around 74,000 individual tiles!

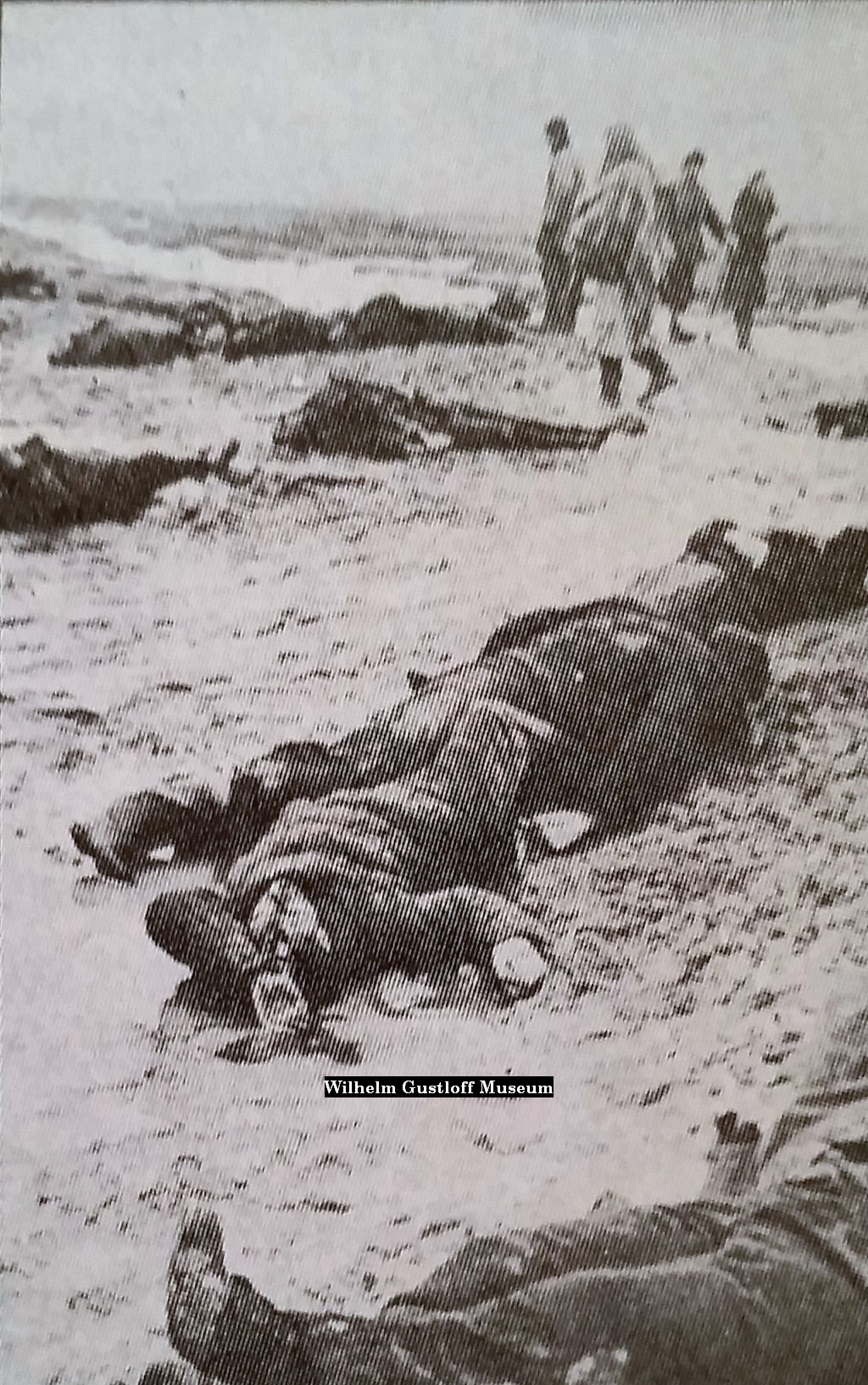

Two of the most graphic images relating to the Wilhelm Gustloff: "Bodies washed ashore along the Pomeranian coastline for weeks after the tragic Gustloff sinking. Most of the victims died from prolonged exposure to the icy waters." This is the same area where the deck wood carved into the Madonna was discovered laying on the beaches among the dead.

The Hansa was docked next to the Wilhelm Gustloff in Gotenhafen during the war and left with her on the fateful night of January 30th, 1945. She was forced to return due to mechanical trouble and returned to port. After being used to evacuate refugees, on March 6th, she hit a mine off Warnemünde and capsized near the harbor entrance in shallow water. The starboard side of its hull sticking up 5 meters from the water. The ship was eventually uprighted and made able to float again (photo) before being taken to the port of Warnemünde on December 15, 1949 for her conversion into a new passenger ship (above right). She was delivered to the Soviet Union in 1955 as the Sovetskiy Soyuz and scrapped in 1982.

The last three photos come from the Belgian - German diving expedition that recovered the tile mosaic. Their ship, the M.S. Michael Glinka, in port. Working to raise the tile and other items from the wreck. The tile on deck just after it was recovered. The diver told me he when he found it in the mud, he touched it and the mud cleared away to reveal the piece. All they had to do once the tile was on deck was to rinse it off with sea water and it looked like new.

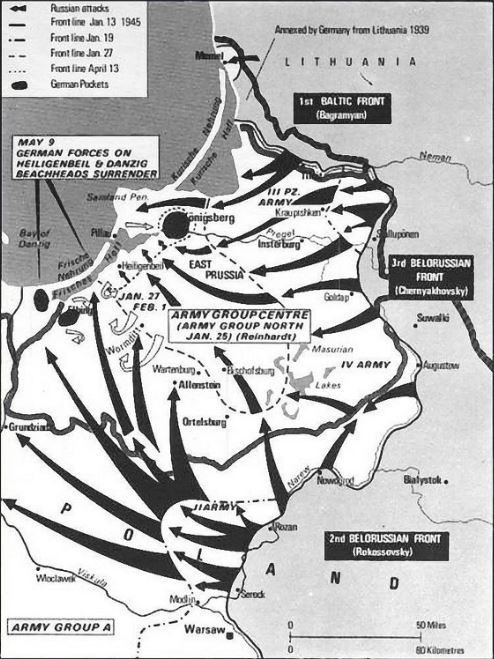

January, 1945 - Gotenhafen. Full-fledged panic is erupting in East Prussia. Tales of Russian revenge for the Nazi invasion of the Motherland spread like wildfire all the way to the Wilhelm Gustloff's port in Gotenhafen's Oxhöft Pier. Hundreds of thousands of German refugees continue to stream in to the Danzig, hoping for safe passage to the West. Alarm widens even more after news of massacres in Nemmersdorf filters through. On a counteroffensive, the German 4th Army managed to temporarily recapture Nemmersdorf, the first town within German borders to be run-over by the Soviets in October 1944. Nazi news agencies are quick to document the Soviet brutality. Newsreels exhibit horrifying images of rape and murder (especially women and children) with the hope that the world will be appalled over the brutality of the Bolsheviks. It was also hoped after seeing these images, Germans would rise up to exact revenge on the Soviets for their actions. A defiant Hitler hysterically calls for all able-bodied men to defend Germany. Many of these "men" are boys as young as 15 or senior citizens of the Volksstrum - Hitler's desperately assembled homeland defense army where any male capable of fighting was thrown into battle (often with only a gun and an armband to identify them).

The western world was not sympathetic and rather than rise up against the Soviets, the footage caused mass panic. Newsreels, newspapers, radio reports, and tales of Red Army carnage only serve to intensify the panic within eastern greater Germany. From the decks of the Wilhelm Gustloff, sounds of advancing artillery grow louder with each passing day. Despite heroic efforts to hold the front, the Reich is collapsing. A major offensive launched by the Soviets in mid-January accelerates the exodus from East Prussia. Many ethnic Germans cut off from the Danzig by the Red

The western world was not sympathetic and rather than rise up against the Soviets, the footage caused mass panic. Newsreels, newspapers, radio reports, and tales of Red Army carnage only serve to intensify the panic within eastern greater Germany. From the decks of the Wilhelm Gustloff, sounds of advancing artillery grow louder with each passing day. Despite heroic efforts to hold the front, the Reich is collapsing. A major offensive launched by the Soviets in mid-January accelerates the exodus from East Prussia. Many ethnic Germans cut off from the Danzig by the Red

Army troops negotiate passage across the frozen Frisches Haff, a freshwater lagoon on the Baltic coast. Soviet planes circle in the sky, bombing defenseless refugees. Direct hits are not necessary - weakening the ice is enough to send families with their wagons and horses through to an icy death. To the many refugees streaming toward ports in the Danzig, escape to the West is the only hope of avoiding certain suffering and death. Hitler's brutal 'war of extermination' that begun in June 1941 in the East and causing unprecedented human suffering - has turned upon him with a vengeance.

Operation Hannibal

Hope is in the form of Operation Hannibal. Eventually to become the most successful wartime evacuation in history, Hannibal will be responsible for transporting 2 million Germans safely to the West. Despite Hitler's refusal to yield an inch, Gross Admiral Karl Dönitz of the Navy manages to send the one word coded signal "HANNIBAL" on January 21st for his submariners to flee to the West. Unlike Hitler, Dönitz accepts the true nature of the desperate situation and uses this opportunity to evacuate all Germans possible - including refugees.

On January 22nd, 1945, the Gustloff begins preparations to accept thousands of refugees. There are also obvious challenges involved in getting the ship running properly. With the exception of minor test runs, the Gustloff's engines have not been operated in over 4 years. Ships of all shapes and sizes are assembled and prepared for sailing West. Joining the Wilhelm Gustloff will be the ships Cap Arcona, Robert Ley, Hamburg, Hansa, Deutschland, Potsdam, Pretoria, Berlin, General von Steuben, Monte Rosa, Antonio Delfino, Winrich von Kniprode, Ubena, Goya, along with numerous cargo vessels down to tug boats. All are directly under the command of Donitz to ensure urgency.

The Soviet Submarine

Meanwhile, a maverick submarine captain with the Soviet Navy arrives in Gulf of Danzig waters. Captain Alexander Marinesko of the Soviet submarine S-13 is under the gun. On January 2nd, 1945 he is supposed to leave port in Turku, Finland to patrol the Baltic with a team of three other Soviet subs. Unfortunately, his New Year's Eve celebrations go out of control. He disappears on December 31st, 1944 for a three-day binge on alcohol and brothels. Despite all efforts of his shielding crew, they cannot locate him.

At sea, Marinesko is a skilled and decisive submarine captain who enjoys the admiration and devotion of his crew - and never touches a drop of alcohol. On land, he is volatile and impulsive, with a history of drinking beyond excess. The crew finally locates him, dries him out in a sauna, and returns him to base one day after the other subs have left.

Soviet security forces (NKVD - precursor to the KGB) are livid and suspect Marinesko of treachery. They want him court martialed. On the other hand, the Navy is more "forgiving". Stalin has pressured the Navy for all possible resources deployed to destroy the facists. His loyal crew wants him back and could cause even more problems if denied. Finally, after numerous days of interrogation and waiting in limbo, Marinesko heads out to the Baltic aboard the S-13 on January 11th, 1945. He still commands his vessel at sea,

Operation Hannibal

Hope is in the form of Operation Hannibal. Eventually to become the most successful wartime evacuation in history, Hannibal will be responsible for transporting 2 million Germans safely to the West. Despite Hitler's refusal to yield an inch, Gross Admiral Karl Dönitz of the Navy manages to send the one word coded signal "HANNIBAL" on January 21st for his submariners to flee to the West. Unlike Hitler, Dönitz accepts the true nature of the desperate situation and uses this opportunity to evacuate all Germans possible - including refugees.

On January 22nd, 1945, the Gustloff begins preparations to accept thousands of refugees. There are also obvious challenges involved in getting the ship running properly. With the exception of minor test runs, the Gustloff's engines have not been operated in over 4 years. Ships of all shapes and sizes are assembled and prepared for sailing West. Joining the Wilhelm Gustloff will be the ships Cap Arcona, Robert Ley, Hamburg, Hansa, Deutschland, Potsdam, Pretoria, Berlin, General von Steuben, Monte Rosa, Antonio Delfino, Winrich von Kniprode, Ubena, Goya, along with numerous cargo vessels down to tug boats. All are directly under the command of Donitz to ensure urgency.

The Soviet Submarine

Meanwhile, a maverick submarine captain with the Soviet Navy arrives in Gulf of Danzig waters. Captain Alexander Marinesko of the Soviet submarine S-13 is under the gun. On January 2nd, 1945 he is supposed to leave port in Turku, Finland to patrol the Baltic with a team of three other Soviet subs. Unfortunately, his New Year's Eve celebrations go out of control. He disappears on December 31st, 1944 for a three-day binge on alcohol and brothels. Despite all efforts of his shielding crew, they cannot locate him.

At sea, Marinesko is a skilled and decisive submarine captain who enjoys the admiration and devotion of his crew - and never touches a drop of alcohol. On land, he is volatile and impulsive, with a history of drinking beyond excess. The crew finally locates him, dries him out in a sauna, and returns him to base one day after the other subs have left.

Soviet security forces (NKVD - precursor to the KGB) are livid and suspect Marinesko of treachery. They want him court martialed. On the other hand, the Navy is more "forgiving". Stalin has pressured the Navy for all possible resources deployed to destroy the facists. His loyal crew wants him back and could cause even more problems if denied. Finally, after numerous days of interrogation and waiting in limbo, Marinesko heads out to the Baltic aboard the S-13 on January 11th, 1945. He still commands his vessel at sea,

but needs a big score to mitigate his misdeeds while on land. He will find it soon enough.

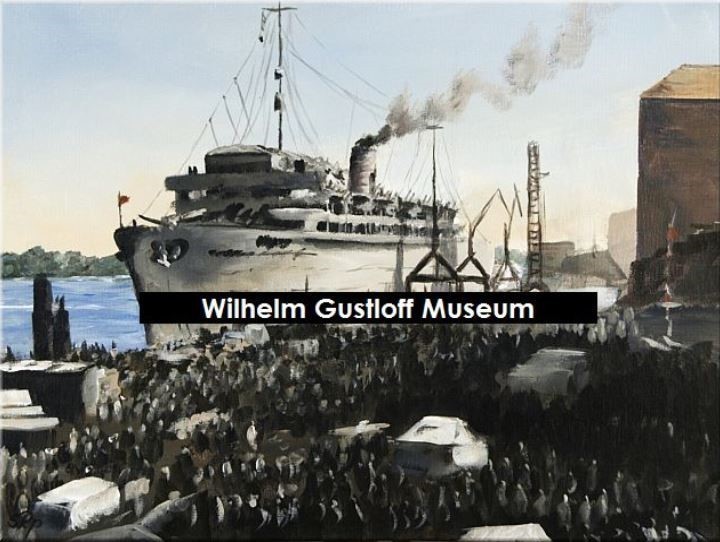

The Wilhelm Gustloff - The Ship of Hope

The "German Dunkirk" spearheaded by Gross Admiral Donitz is about to begin. The Wilhelm Gustloff once again finds itself in the role as flagship in Gotenhafen. This time however, it is not a gleaming white flagship of the KdF cruise program. It is a naval gray ship of hope for anxious throngs of refugees who are lucky enough to make it as far as the docks. On January 28th, 1945, the Wilhelm Gustloff is ordered to be ready to leave within 48 hours.

The scene in Gotenhafen is panic-laced chaos. Thousands and thousands of refugees - mostly women and children - jam the harbor. You won't find many able-bodied men. Those who can fight the Russians have already been procured for duty (feared SS Stormtroopers patrolling the crowds ensure none are overlooked). Many are not well - having endured bitter cold and long distances by carriage or foot in unforgiving January weather. Thousands do not make it to the Danzig ports. Unimaginable death litters the roadsides and in places like the frozen Frisches Haff lagoon. Despite the mass of pulsating humanity on the docks, boarding the Gustloff is relatively orderly in the early stages. In the standard Nazi-style, originally people were required to have a

The Wilhelm Gustloff - The Ship of Hope